Month: January 2024

Courtney McKinney-Whitaker • Derry Member

January 25, 2024Last week, we discussed how Presbyterians from southern Scotland migrated to Ulster, Ireland’s northernmost province, and became known as the Ulster Scots. To summarize, in the early 1600s, England determined to strengthen its grip on Ulster through a policy of plantation (or settler-colonialism). English landlords found tenants for their holdings among the Presbyterians of southern Scotland, for whom repeated crop failures and religious persecution made Scotland a difficult place to live. Some Scottish Presbyterians settled in Ulster on the chance life might be easier there, but some were forced to emigrate.

Now we’ll look at how many Ulster Scots found themselves emigrating a second time in relatively short order, not simply across the narrow channel that divides Ulster from southern Scotland, but across the Atlantic Ocean.

The Siege of Londonderry

Toward the end of the 17th century, Ireland became a minor theater in a larger struggle known variously as the War of the League of Augsberg, the War of the Grand Alliance, the Nine Years’ War, King William’s War, and the War of the Three Kings (1688-1697). To summarize, the French Catholic monarch Louis XIV sought to extend his power and smaller (largely Protestant) nations banded together to stop him.

Louis XIV was the first, and certainly the most powerful, of the three kings referenced. The two others were the Catholic James II of England (also James VII of Scotland) and Protestant Dutch Prince William of Orange. William was both James’s nephew and son-in-law, as he was married to his first cousin, James’s daughter Mary.

Despite persecution from Protestant reformers, the Catholic presence in England had never disappeared. After Oliver Cromwell’s death, his Commonwealth government collapsed and the Stuart dynasty was restored to the English throne in the person of Charles II, son of the executed monarch Charles I. While Charles II produced many children with his mistresses, his marriage was childless, so his openly Catholic younger brother James inherited the throne upon his death in 1685.

When James’s Catholic second wife gave birth to a son in June 1688, panic arose among Protestants across both islands at the thought of a Catholic dynasty. When William of Orange invaded England in November 1688, the English army and navy supported him and James escaped to France.

In England, Parliament declared that James had abdicated through desertion and offered William and Mary the crown as co-regents ruling as William III and Mary II. James attempted to reclaim his throne by bringing a French army to Ireland. In Ireland, the larger-scale European conflict between Protestant and Catholic powers played out between Jacobite (Latin for James) forces who favored the Catholic James II and VII’s claim to the thrones of England, Scotland, and Ireland and Williamite forces who favored William of Orange.

As Protestants, the Ulster Scots were firmly in the Williamite camp. The Siege of Londonderry is probably the most lauded moment in Ulster Scots history. In 1689, they made their most famous stand as they held the walled city of Londonderry against Jacobite forces for 105 days at great personal cost, contributing mightily to William’s ultimate victory at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690.

In the ensuing years, many more Presbyterians left Scotland to join the Ulster Scots Presbyterians in Ireland. Alas, any belief that their contributions to the Williamite victory would lead to political and religious equality with Anglicans was short-lived. By 1704, the more religiously tolerant (and perhaps grateful) William III was dead, along with his wife and co-regent Mary II. In that year, the Test Acts went into effect, requiring all public office holders to produce a certificate stating they had received communion in an Anglican church, effectively barring Presbyterians from government.

Emigration to North America

In the 18th century, many elements combined to make emigration to North America attractive to the Ulster Scots. The Crown and the Anglican Church regarded their marriages as invalid, excluded them from public life, and required them to pay additional taxes. They were accustomed to religious intolerance, and that alone might not have induced them to leave Ulster. But crop failures, rising rents, and a string of economic crises made the prospect of a new land more appealing.

Kevin Kenny writes, “Presbyterians began to leave Ulster for America in large numbers at the turn of the eighteenth century. They left in pursuit of land and religious toleration, the two goals that had brought their Scottish forefathers to Ulster over the previous three generations” (27). In the early decades of the eighteenth century, Pennsylvania was the most religiously tolerant of Great Britain’s North American colonies, an appealing prospect for dissenters from the Church of England, including Presbyterians. (In 1707, the Treaty of Union established the Kingdom of Great Britain as a sovereign nation by uniting the Kingdom of England, which included Wales from 1542, and the Kingdom of Scotland.)

In 1718, large-scale Ulster Scots migration to North America began with the departure from Derry Quay of five ships carrying several congregations of Presbyterians led by their ministers. Landing in Boston, they found the long-established Puritan inhabitants hostile. As early as 1700, noted Puritan minister Cotton Mather had declared attempts at Ulster Scots settlement in New England to be “formidable attempts of Satan and his Sons to Unsettle us”(28). By 1724, the traditional date of Derry Church’s founding, new Ulster Scots immigrants to North America had learned to look for homes further south, a process facilitated by close ties between Belfast merchants and Delaware ports.

For the third time in history, the people who had been the Lowland Scots and who had become the Ulster Scots, would take on a new frontier and a new name. “On both sides of the Atlantic, Ulster Presbyterians served as a military and cultural buffer between zones of perceived civility and barbarity, separating Anglicans from Catholics in Ireland and eastern elites from Indians in the American colonies. What they wanted above all else was personal security and land to call their own” (3). In North America, the Ulster Scots became known as the Scots-Irish, and would again serve as a human shield between elite colonizers and indigenous people, at the mercy of, and ultimately reviled by, both.

This was the world into which Derry Church came into being, a world whose true nature has been cloaked over time in the myth of brave and hearty frontiersmen and women. No doubt some of them were brave and hearty, and certainly most of them clung to their own interpretation of the Presbyterian faith as a comfort and a guide in a world in which their lives were likely to be short and difficult and to end messily. Conditions on the North American frontier were brutal, and the choices these largely impoverished and repeatedly oppressed people faced were often no choice at all. Sometimes their migration was forced. Often they were lied to about the opportunities awaiting them on the opposite side of a perilous sea voyage.

The Ulster Scots who made their way to North America were victims of the generational trauma of living a hardscrabble existence on frontiers, between warring forces, their homes never secure, their lives perpetually at risk. By the time they came to the place they called Derry Church, they were ready to fight for their own security, whether that meant fighting the people who were already here or the elites who forced them onto the frontier.

Perhaps for our 300th Anniversary, we can give our forebears the gift of seeing them truly, with the mix of pride, shame, and compassion which is the legacy of most of the people who have walked this earth.

Further Reading: The best secondary source on this topic is Kevin Kenny’s Peaceable Kingdom Lost: The Paxton Boys and the Destruction of William Penn’s Holy Experiment, from which the above quotations are taken.

Courtney McKinney-Whitaker • Derry Member

January 18, 2024Spend enough time around Derry Church, and you’ll hear the story of how our earliest members emigrated from Ireland to Pennsylvania in the early 1700s, founding a church here around 1724. In this first piece, I’m taking you deeper into the past, to an earlier migration that is just as deserving of a place in Derry’s collective memory.

The Protestant Reformation

Derry’s story begins with the Protestant Reformation. In 1517, priest and theologian Martin Luther published his 95 Theses, challenging the teachings of the Catholic church and inadvertently igniting the religious reform movement known as the Protestant Reformation. Religious groups in conflict with the Catholic church soon came into conflict with each other, ultimately producing the many denominations of Protestantism known to us today, including Presbyterianism.

While the Protestant Reformation occurred across Europe, events in England are most significant for Derry. In 1534, the infamous English monarch Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic Church and established the Church of England, or Anglicanism. Henry VIII’s concerns were political, not religious. While the English monarch replaced the pope as the head of the church, Anglicanism remained similar to Catholicism.

Henry VIII’s actions produced two significant outcomes in England. First, it left serious religious reformers interested in a change in church substance, not just in name and leadership, dissatisfied. Second, by creating a national church, it explicitly tied religious identity to national identity. Those who didn’t support the national church might find themselves under suspicion of not supporting the nation—and by extension, the monarch who was head of both.

Scottish Presbyterianism vs. English Anglicanism

Meanwhile in Scotland, Protestant zealot John Knox spread the teachings of Swiss theologian Jean (or John) Calvin. In Scotland, national identity became linked to Calvinism, a theology most fully expressed in Presbyterianism. The first General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church was held in Edinburgh in December 1560. Over the next century, an early form of Presbyterianism comprised of a combination of Anglican, Puritan, and Calvinist theology, structure, and process spread throughout southern Scotland. (The much-mythologized Highlands and its clans remained overwhelmingly Catholic and separate from the Lowlands. They are not a significant part of Derry Church’s story.)

In 1603, James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of his cousin Elizabeth I of England, making him both King of Scots and King James I of England. (The two remained separate nations, but James was king of both, reigning as James VI of Scotland and James I of England.) James had been baptized Roman Catholic and raised Presbyterian, but he understood that his throne and his global power depended on that of the more powerful nation of England and its Anglican church. This led to a series of attempts by James and his heirs to “Anglicize” Scottish Presbyterianism and bring the two nations into closer alignment.

In 1637, attempts by James’s son Charles I to impose Anglicanism in Scotland led to riots in the Presbyterian stronghold of St. Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh. A more measured response to Charles I’s actions came in the form of the Scottish National Covenant of 1638, which declared Presbyterianism to be the only true form of church government and aligned Scotland with Presbyterianism and the principles of the Protestant Reformation. Over 300,000 Presbyterians in Scotland and Ulster signed it.

The Presbyterian Migration to Ulster

Where is Ulster, and what were Scottish Presbyterians doing there? To answer that question, let’s start with a little geography.

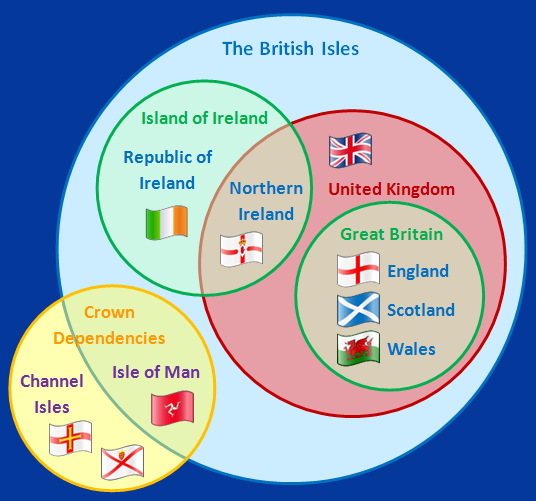

Ireland is the name of a nation, but it’s also the name of an island, and the two aren’t exactly the same. Today, the separate nations of the Republic of Ireland (commonly called “Ireland” and a completely independent nation) and Northern Ireland (which is part of the United Kingdom) share the island of Ireland.

Ulster is one of the four traditional provinces that make up the island of Ireland. Northern Ireland is comprised of six counties in Ulster. But three of Ulster’s counties are in the Republic of Ireland. The island’s traditional provinces predate English interference and have no present-day political existence or administration—and what existed in the past wasn’t especially strong. It might be helpful to think of these traditional provinces as similar to regions—such as New England, the Southeast, the Midwest—in the United States. These areas have a shared history and culture, but they aren’t political entities.

Okay, back to the history:

English monarchs had been claiming Ireland since at least the 1100s, but much of their power was in name only. In the early decades of the 1600s, the English Crown’s attempts to rule Ireland in fact as well as in name led to the systematic plantation of Ulster, the northernmost province of Ireland that had always been the most difficult to bring under English control. In this context, “plantation” is a verb, not the noun we’re used to using to refer to large antebellum farms in the American Southeast. In essence, plantation involves driving the native inhabitants off the land you want and replacing them, or simply overwhelming them, with your own people. England used this method (which is very similar to what is today called “settler-colonialism”) to great effect for centuries, with Ulster as their proving ground.

So why did the Plantation of Ulster occur when it did? With much of Ulster abandoned by native Irish leaders as a result of conflicts early in the 1600s, English interests were able to swoop in and sell the abandoned land to new (mostly English) landlords. In need of tenants to make their new holdings profitable, these landlords looked to the Lowlands of Scotland, where years of crop failures and religious persecution for their Presbyterian faith made promises of better land and greater religious toleration in Ulster attractive. Some of these Scottish settlers in Ulster chose migration—to the extent that trading probable starvation for possible starvation is a choice. However, some were forcibly transplanted.

In addition to their vulnerable state as a mostly poor and marginalized group, Lowlander Scots held a particular attraction for their new landlords. For centuries, their families had inhabited the constantly contested borderlands of England and Scotland. They were accustomed to making their homes between violently antagonistic forces. This was key, because the land they settled on was not empty. Ulster had been abandoned only by its elites. Many native Irish remained, clinging to their Catholic faith in the face of persecution from both English Anglican landlords and Scottish Presbyterian tenants.

The Black Oath

When those 300,000 Presbyterians in Scotland and Ulster signed the Scottish National Covenant of 1638, the English Crown responded with what became known as the “Black Oath.” It required every Protestant in Scotland and Ulster over the age of sixteen to swear allegiance to the king and reject the Scottish National Covenant. The Black Oath turned the Ulster Scots community against Charles I, adding to the controversial monarch’s many enemies. The 1640s, a decade of bloody unrest on both islands, ended with the king’s execution in 1649.

When the dust of migration and war finally cleared around 1660 there were three major religious groups in Ulster: displaced and oppressed Catholics, looking to Rome and the Catholic monarchs of continental Europe for redemption; land-owning Anglicans, loyal to the restored monarch Charles II and the Church of England; and a tenant class of Protestant Dissenters, of which Scottish Presbyterians made up the largest part and whose numbers were increasing.

Indeed, while there had been plenty of Scottish Presbyterian settlements in Ulster in the first half of the 1600s, the greatest numbers, including many Presbyterian ministers, migrated to Ireland during the second half. All told, perhaps a quarter of a million people migrated from the island of Great Britain (England, Wales, and Scotland) to the island of Ireland by 1700, most of them to Ulster.

These migrants to Ulster from Lowland Scotland—Scottish, Presbyterian, Dissenters — became known as the Ulster Scots. Stay tuned next week to discover how they became known in North America as the Scots-Irish.

Further Reading: This article provides an extremely simplified overview of a complex historical process. Jonathan Bardon is a major authority on the history of Ulster. His book, The Plantation of Ulster (2011) is the standard source. If you’re not interested in reading a whole book but want to learn a bit more, check out the Ulster-Scots Agency.

Image credit: Wdcf, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Eleanor Schneider • Derry Member

January 11, 2024

We are nearing the end of a season of wonder and I confess I have never ceased to be amazed at the number of projects and their huge impact for our local and worldwide communities that Derry undertakes. I say this because my first church was a small congregation in western Pennsylvania where I remember hearing adults talk about “living link missionaries.” These missionaries seemed to be far away, so I wondered: where were these missionaries and what did they do there?

My experience of mission at Derry has vastly enlarged my understanding of how we, individually and collectively, are a link to others. I am thinking especially of the ministry of the Presbyterian Education Board (PEB) in Pakistan, which Derry members have been supporting — first in small ways beginning in 2009, and now in significantly substantial ways through a variety of fundraising endeavors and the personal involvement of many. This is about education for the most needy in Pakistan, where government-run schools are inadequate and where many children could suffer lifelong illiteracy.

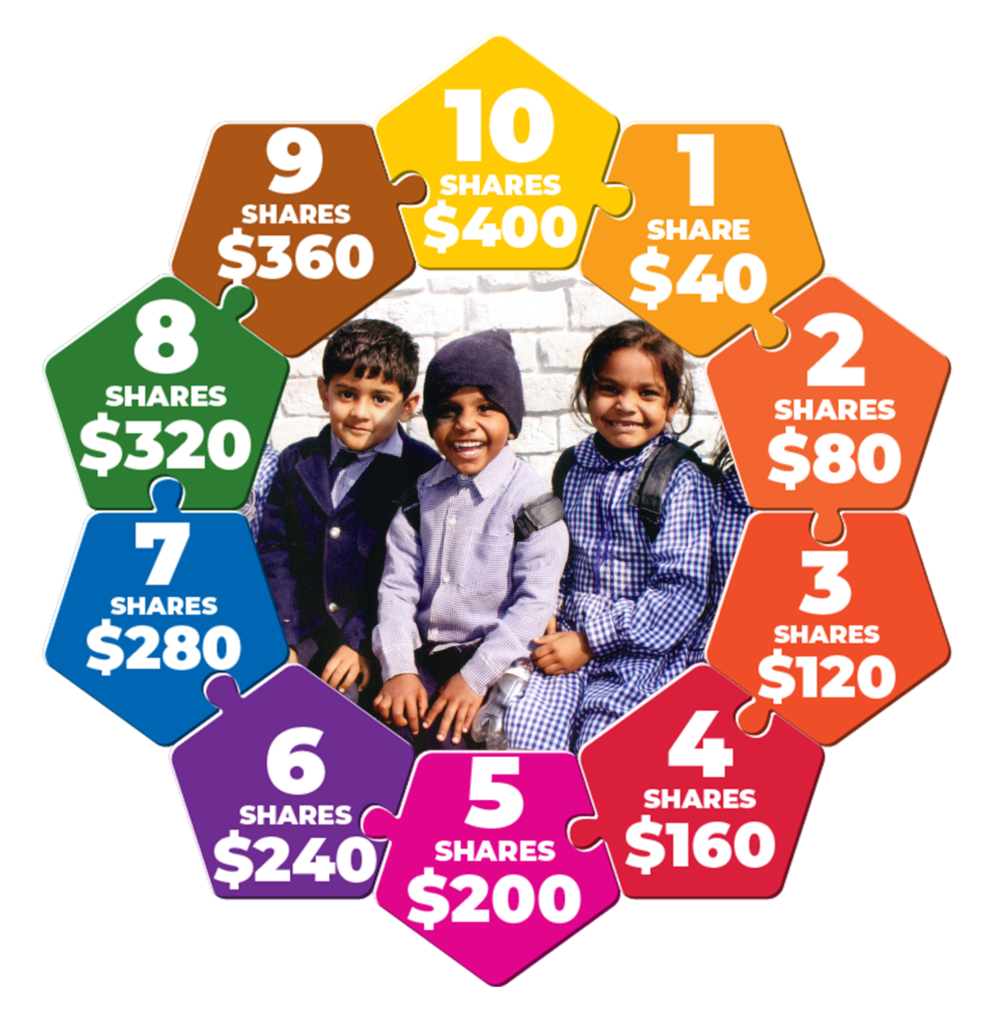

Derry’s Shares for Scholarships campaign, under way now and continuing through February, supports the education of children in PEB schools. Last year 54 folks at Derry raised $23,200 in scholarship funds that are benefiting 55 children who attend PEB day and boarding schools. It is my good fortune and a blessing to be able to send Adan, a little guy who is a day student, to nursery school. His letter from 2022 tells me that his favorite subject is English and that he wants to be an engineer. Wonderful!

Derry members support the work of PEB through Friends of the Presbyterian Education Board here and across the country. There are now three schools in Sargodha (a large city of about 660,000 people) that serve more than 1,000 boys and girls who are Christians and Muslims. An annual scholarship is $400 for a day student and $800 for a boarding student. A share is any amount you might wish to allow God, though you, to support the education of a child.

I believe we are truly God’s links to youngsters who will have hope of a better future, a chance to rise out of poverty, and the promise of becoming educated citizens who are prepared to serve their communities and the world. A card from PEB reminded me of Hebrews 6:1, “God is not unjust: God will not forget your work and the love you have shown him as you have helped God’s people and continue to help them.”

I invite you to join me by becoming a link of God’s love to one of God’s children by giving online or by sending checks to Derry Church notated “Pakistan Scholarships.”

Marilyn Koch • Derry Member

January 4, 2024Editor’s Note: On the first Thursday of each month (or close to it), the eNews feature article highlights the mission focus for the month. In January we’re lifting up women’s equality, justice and opportunity through the good work of our mission partner, Bethesda Women and Children’s Mission in Harrisburg.

My first visit to Bethesda Women’s Shelter was easily 25 years ago. It was a dark, cramped building that had once been a school. We shared our love by preparing a luncheon and sharing a meal together. Over time, Derry members visited and learned about their programs and needs, and we planted colorful geraniums in a narrow strip of grass between the sidewalk and the road.

Now the Shelter has been replaced on the same site by a light-filled interior space surrounded by outdoor views that allow women to thrive in a Christ-centered facility. Bethesda offers hope to those searching for their purpose and their place in this world.

On completion of a year-long Discipleship and Recovery program, women have the option to move into a Transitional Living Program before moving out on their own. Because many of the women have addictions to drugs and alcohol, and may have been living in domestic abuse situations, it is important for program participants to commit to sobriety. Bethesda offers prayer, a discipleship program, counseling — individual and group — and 12-step Christian recovery groups and meetings. Children may stay with their mothers at the shelter so their bond can be maintained and strengthened. Parenting classes are available, and everyone has access to financial and budgeting instruction to help round out their life skills.

Since their education may have been interrupted, Bethesda can assist participants in obtaining local social, medical, and educational services to help them set and reach attainable goals during their stay. Some women, after completing Bethesda’s programming, either return to the work force or continue their education at a local college. Many of the graduates remain in contact with the shelter through calls, mentoring, or as volunteers.

Derry has shared our love with them as well as our mission funds over the years. Look for opportunities in the near future for you to share your time and talents, too!