Weekly Article

Courtney McKinney-Whitaker • Derry Member

January 18, 2024Spend enough time around Derry Church, and you’ll hear the story of how our earliest members emigrated from Ireland to Pennsylvania in the early 1700s, founding a church here around 1724. In this first piece, I’m taking you deeper into the past, to an earlier migration that is just as deserving of a place in Derry’s collective memory.

The Protestant Reformation

Derry’s story begins with the Protestant Reformation. In 1517, priest and theologian Martin Luther published his 95 Theses, challenging the teachings of the Catholic church and inadvertently igniting the religious reform movement known as the Protestant Reformation. Religious groups in conflict with the Catholic church soon came into conflict with each other, ultimately producing the many denominations of Protestantism known to us today, including Presbyterianism.

While the Protestant Reformation occurred across Europe, events in England are most significant for Derry. In 1534, the infamous English monarch Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic Church and established the Church of England, or Anglicanism. Henry VIII’s concerns were political, not religious. While the English monarch replaced the pope as the head of the church, Anglicanism remained similar to Catholicism.

Henry VIII’s actions produced two significant outcomes in England. First, it left serious religious reformers interested in a change in church substance, not just in name and leadership, dissatisfied. Second, by creating a national church, it explicitly tied religious identity to national identity. Those who didn’t support the national church might find themselves under suspicion of not supporting the nation—and by extension, the monarch who was head of both.

Scottish Presbyterianism vs. English Anglicanism

Meanwhile in Scotland, Protestant zealot John Knox spread the teachings of Swiss theologian Jean (or John) Calvin. In Scotland, national identity became linked to Calvinism, a theology most fully expressed in Presbyterianism. The first General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church was held in Edinburgh in December 1560. Over the next century, an early form of Presbyterianism comprised of a combination of Anglican, Puritan, and Calvinist theology, structure, and process spread throughout southern Scotland. (The much-mythologized Highlands and its clans remained overwhelmingly Catholic and separate from the Lowlands. They are not a significant part of Derry Church’s story.)

In 1603, James VI of Scotland inherited the throne of his cousin Elizabeth I of England, making him both King of Scots and King James I of England. (The two remained separate nations, but James was king of both, reigning as James VI of Scotland and James I of England.) James had been baptized Roman Catholic and raised Presbyterian, but he understood that his throne and his global power depended on that of the more powerful nation of England and its Anglican church. This led to a series of attempts by James and his heirs to “Anglicize” Scottish Presbyterianism and bring the two nations into closer alignment.

In 1637, attempts by James’s son Charles I to impose Anglicanism in Scotland led to riots in the Presbyterian stronghold of St. Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh. A more measured response to Charles I’s actions came in the form of the Scottish National Covenant of 1638, which declared Presbyterianism to be the only true form of church government and aligned Scotland with Presbyterianism and the principles of the Protestant Reformation. Over 300,000 Presbyterians in Scotland and Ulster signed it.

The Presbyterian Migration to Ulster

Where is Ulster, and what were Scottish Presbyterians doing there? To answer that question, let’s start with a little geography.

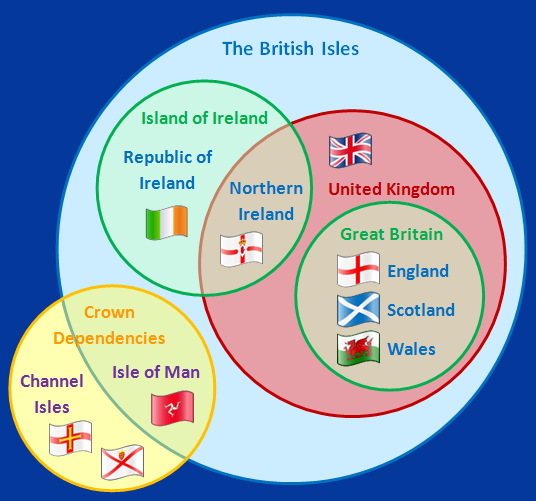

Ireland is the name of a nation, but it’s also the name of an island, and the two aren’t exactly the same. Today, the separate nations of the Republic of Ireland (commonly called “Ireland” and a completely independent nation) and Northern Ireland (which is part of the United Kingdom) share the island of Ireland.

Ulster is one of the four traditional provinces that make up the island of Ireland. Northern Ireland is comprised of six counties in Ulster. But three of Ulster’s counties are in the Republic of Ireland. The island’s traditional provinces predate English interference and have no present-day political existence or administration—and what existed in the past wasn’t especially strong. It might be helpful to think of these traditional provinces as similar to regions—such as New England, the Southeast, the Midwest—in the United States. These areas have a shared history and culture, but they aren’t political entities.

Okay, back to the history:

English monarchs had been claiming Ireland since at least the 1100s, but much of their power was in name only. In the early decades of the 1600s, the English Crown’s attempts to rule Ireland in fact as well as in name led to the systematic plantation of Ulster, the northernmost province of Ireland that had always been the most difficult to bring under English control. In this context, “plantation” is a verb, not the noun we’re used to using to refer to large antebellum farms in the American Southeast. In essence, plantation involves driving the native inhabitants off the land you want and replacing them, or simply overwhelming them, with your own people. England used this method (which is very similar to what is today called “settler-colonialism”) to great effect for centuries, with Ulster as their proving ground.

So why did the Plantation of Ulster occur when it did? With much of Ulster abandoned by native Irish leaders as a result of conflicts early in the 1600s, English interests were able to swoop in and sell the abandoned land to new (mostly English) landlords. In need of tenants to make their new holdings profitable, these landlords looked to the Lowlands of Scotland, where years of crop failures and religious persecution for their Presbyterian faith made promises of better land and greater religious toleration in Ulster attractive. Some of these Scottish settlers in Ulster chose migration—to the extent that trading probable starvation for possible starvation is a choice. However, some were forcibly transplanted.

In addition to their vulnerable state as a mostly poor and marginalized group, Lowlander Scots held a particular attraction for their new landlords. For centuries, their families had inhabited the constantly contested borderlands of England and Scotland. They were accustomed to making their homes between violently antagonistic forces. This was key, because the land they settled on was not empty. Ulster had been abandoned only by its elites. Many native Irish remained, clinging to their Catholic faith in the face of persecution from both English Anglican landlords and Scottish Presbyterian tenants.

The Black Oath

When those 300,000 Presbyterians in Scotland and Ulster signed the Scottish National Covenant of 1638, the English Crown responded with what became known as the “Black Oath.” It required every Protestant in Scotland and Ulster over the age of sixteen to swear allegiance to the king and reject the Scottish National Covenant. The Black Oath turned the Ulster Scots community against Charles I, adding to the controversial monarch’s many enemies. The 1640s, a decade of bloody unrest on both islands, ended with the king’s execution in 1649.

When the dust of migration and war finally cleared around 1660 there were three major religious groups in Ulster: displaced and oppressed Catholics, looking to Rome and the Catholic monarchs of continental Europe for redemption; land-owning Anglicans, loyal to the restored monarch Charles II and the Church of England; and a tenant class of Protestant Dissenters, of which Scottish Presbyterians made up the largest part and whose numbers were increasing.

Indeed, while there had been plenty of Scottish Presbyterian settlements in Ulster in the first half of the 1600s, the greatest numbers, including many Presbyterian ministers, migrated to Ireland during the second half. All told, perhaps a quarter of a million people migrated from the island of Great Britain (England, Wales, and Scotland) to the island of Ireland by 1700, most of them to Ulster.

These migrants to Ulster from Lowland Scotland—Scottish, Presbyterian, Dissenters — became known as the Ulster Scots. Stay tuned next week to discover how they became known in North America as the Scots-Irish.

Further Reading: This article provides an extremely simplified overview of a complex historical process. Jonathan Bardon is a major authority on the history of Ulster. His book, The Plantation of Ulster (2011) is the standard source. If you’re not interested in reading a whole book but want to learn a bit more, check out the Ulster-Scots Agency.

Image credit: Wdcf, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons