Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen: District Six

October 11, 2022

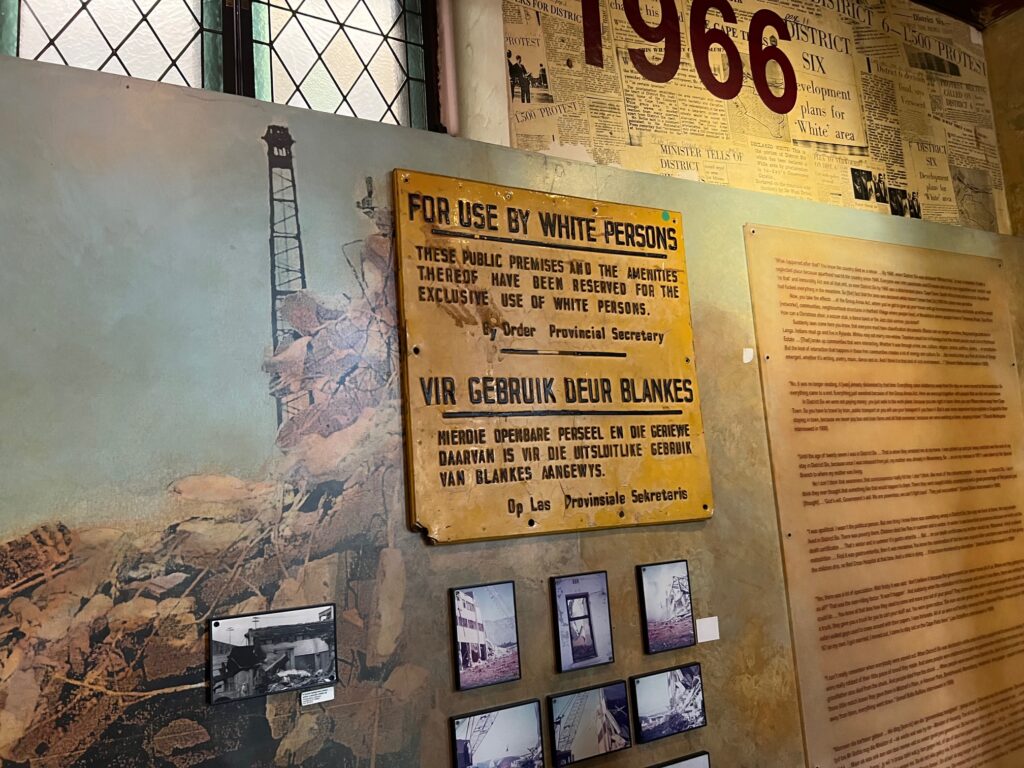

I had the opportunity to visit the District Six Museum in Cape Town and tour it with a former resident. The museum is located in an old Methodist church that survived the destruction of the area. It’s odd because all around you can see the modern skyline of Capetown and nice cafes, but the scars of apartheid still exist in dilapidated buildings and lifeless vacant spaces in the midst of an otherwise bustling city. District Six was one a thriving melting pot, a community where everyone knew their neighbors. Generations had lived there together.

The vacant lots are the remnants of the forced removals which took place in District Six in the 1970s.

The area known as District Six got its name from having been the Sixth Municipal District of Cape Town in 1867. Its earlier unofficial name was Kanaldorp, a name supposedly derived from the the series of canals running across the city, some of which had to be crossed in order to reach the District (kanaal is the Afrikaans for ‘canal’.) Over time, some people called District Six Kanaladorp, (kanala being derived from the Indonesian word for ‘please’), and its likely that the name stems from a fusion of the two meanings.

So what happened in District 6? We have to go way back to understand the not-so-far-back.

Since the 17th century, European colonists coveted South Africa. The Cape of Good Hope, the Southwestern tip of Africa, was once the starting point for ambitious sailors with dreams of arriving in the mysterious East. South Africa was successively colonized by the Dutch in the 17th century and by the British in the 19th century. The discovery of diamonds in the 1860s in Kimberley and the discovery of gold in the 1880s in Witwatersrand and Johannesburg only made the country more attractive to colonists.

People from around the world found a home in the area. District Six, one of the main municipal districts in the center of Cape Town, housed diverse people from Dutch colonies in India, Indonesia and Malaysia. Many Muslims also dwelled in Cape Town, and traveled from Indonesia, the country with the largest Muslim population in the world.

The wealth of religious diversity developed into inclusiveness rather than hostility, said former resident Noor Ebrahim. Ebrahim grew up in District Six and went to a mosque in northern District Six with area families as a child. Today, he works in the District Six Museum and still goes to the mosque from his childhood every day.

“We loved each other in District Six,” Ebrahim said. “When my Christmas comes, they call it Eid. All my friends, Jewish, African, Christian, Hindu, you name it, they would put on a fez, and they would go with me to my mosque. I think that made District Six such a great place.”

The 1950s marked the era of apartheid in South Africa. The government began to racially classify all residents in the country. South Africans were declared white, black, Asian or colored. Most residents of District Six came to be classified as so-called colored or mixed blood. Legislation (including the Population Registration Act, Bantu Education Act, Group Areas Act and Immorality/Mixed Marriages Act) was designed to segregate Europeans from non-Europeans.

“Within that apartheid framework, they thought society would be contaminated by the colored people,” said Joe Schaffers, former resident of District Six and education officer at the District Six Museum.

Classification was arbitrarily based on appearance and judged by government officials. Herman, for instance, spoke Afrikaans and was not initially classified under the system. In 1951, when he was eight years old, he went to have what was called “the pencil test.”

Officials used the test as a way to determine a person’s racial grouping. If a pencil could be run through a person’s hair with ease, a person would be declared white. If the pencil became stuck in a person’s hair, they would be called colored or African. Herman and his parents were categorized as “Cape Colors” as a result of the test.

Although many of Herman’s family members were labeled as colored, his uncle married a white woman and was classified as white. “Many of us rejected that,” Herman said. “They denied their own roots and took on the identity of oppressor, which was the white people. In my family on both sides, there were divisions and people who never really met.”

The subjective nature of the racial groups allowed some people to manipulate the system. Many people took the pencil test in an attempt to be labeled as white since the apartheid system afforded special privilege to this group. White South Africans were given better jobs, education and housing. Some of the White South Africans admitted to looking to the US as a template for their racial discrimination.

The apartheid government took further steps to divide the population following this period of population classification. On Feb. 11, 1966, the government declared District Six to be a white-only residential area under the Group Areas Act. Around 60,000 non-white residents of District Six were forced to move to townships outside of the city center. Residents were moved into the townships according to their racial classification. These townships were located in the dry and dusty Cape Flats area outside the city and often had poor infrastructure.

As a result of these acts, residents could only go to schools, churches and other public spaces reserved for their racial groups. Skin color and bloodlines determined the boundaries of a person’s life. If a white man wanted to visit his wife who had been classified as “colored,” he had to apply for a permit to even enter a colored township, said Schaffers.

Most of District Six’s residents were classified as colored under apartheid. As a result, most residents were affected by the forced removal. Apartments, churches and shops were leveled to the ground in the years after the Group Areas Act. New buildings such as the Cape Peninsula University of Technology were built upon the destroyed buildings, including Ebrahim’s home.

“If you owned property in these areas, they’d ask you to move and offer you a place of lower value,” Schaffers said. “If you refused, they would take this property and offer you an even worse offer than the first one.”

Once people were relocated to the Cape Flats, the government failed to sufficiently support the area’s explosive population. Basic necessities like electricity could be scarce, and the townships breed poverty and gangsters.

“It’s not meeting the needs of people living there,” said Chrischené Julius, manager of Collections in District Six Museum. “It becomes a space that really becomes a symbol as what the Group Areas Act actually achieved.”

Society has gradually improved since apartheid ended in 1994. The current government has pledged to create access to good education and jobs for all people, but change is never swift or complete.

The District Six Museum was established in December 1994 to preserve the memory of District Six and to remember the lessons of segregation. The museum plays a role of education and shows people that the city center is a public space for all people, not a specific race. They focus on people’s stories and memories so the museum is more like a memory box than traditional history museum. Sometimes memory contradicts records, but they allow the memory to remain intact as it is remembered by different residents even if those memories contradict each other. The museum keeps alive the stories and struggles of the residents who lives with the racism and corruption of apartheid.

“The apartheid racism is not something that only white people show towards black people” Julius said. “It’s part of our culture.”

Although the government has issued the Land Restitution Act as a measure to allow former residents to move back into the area, execution is still lagging. Only 200 residents have been able to live back of the 60,000 removed. Many former residents have died, complicating how ownership of the land should be determined. Living expenses in the area in the area are also high, and many who have lived in the Cape Flat area for decades cannot afford to move back to their former lands. The act also fails to address where current residents should relocate and how land covered by new buildings can be allocated to former residents. There are still 1,260 validated claims to land in the area.

Many of the residents feel like they cannot reconcile yet with the government that took them from their homes and neighbors because restitution has not been made. They say it’s an unfair to talk to them about reconciling when the wrongs have not yet been made right. The pain and loss is still very real, so they feel there can it be peace and mercy without any justice. Imagine having so much taken from you, then being asked to just forget it and live in your new, more difficult reality, but also being expected to forgive and let the loss go for the sake of peace. It’s an unfair ask and not one someone who has ever experienced something similar would ever ask. Those kinds of desires and demands on others come from a place of privilege that prioritizes its own peace and well-being over justice.

Learning about District 6 did not feel very foreign to me, as horrible as what happened here was. I grew up learning about forced removal of the Cherokee Nation in my native South Carolina, and many other forced removals of native peoples across the US, so their land could be redeveloped. I’ve learned about redlining and ghettos and the Jim Crow south. We have our own culture of racism, and when we say we are in a post-racist society, we aren’t being honest with our past or our present. We haven’t righted many of the wrongs our society is guilty of, even if we ourselves had no direct role in it. I think we can acknowledge the ways we have improved and progressed, but as in District 6 there is still work to be done. Peace and mercy are important but we need to learn and acknowledge the truth and work for justice if we really believe in reconciliation.