Sabbatical Notes from Pastor Stephen

June 15, 2022June 17

Throughout my sabbatical I’ve been thinking about the power of stories to help us reconcile with one another. Stories are foundational to relationships. When we share our stories, we share our lives. Stories help us experience one another and a snapshot of our very different lives. Experience precedes understanding.

In order to experience one another, we have to be willing to listen. We need to listen with open and gracious hearts, expecting to receive a gift from the other. Stories that are windows into another’s life and experience are always gifts, but we often listen to only respond or trap or so we’ll have our own turn to speak in an effort to change minds or prove our own point.

When we take the time to truly listen to another’s story without an agenda, we receive a gift. Stories are a vehicle to understanding and insight. They’ve always been a way we connect with one another and share hopes, dreams, and even beliefs.

But we need places to tell stories. Places of trust, openness, and inclusion. A place we can engage with one another and hear each other’s stories without judgment or fear or debate because a place of storytelling is a vehicle to a place of engagement.

I’m hoping Derry can become a place of reasoned public discourse. A place where we can share our stories. In order to do this we can’t say anything that doesn’t belong to our own experience, so we don’t quote statistics or share that we read this or that or heard this and this. We share from our own personal experience. And we do not condemn people for their stories, their reasons, or their choices.

I have a few ideas how to start this process. The first is called Engage: Stories. The idea is based off of something started in Northern Ireland called TenX9 where nine people share a ten-minute personal story typically around a common theme. It’s a chance for people to find and share their voice and for others to hear a variety of vastly different personal experiences.

Engage: Stories is a creative space for worship and storytelling. We would invite seven people to share an 8-minute personal story around a central theme inspired by Scripture. The stories must be from personal experiences: this is not a TED talk. After each story there will be a brief period for what I call brave and curious questions. The questions are meant to help you learn more about the experience, not to challenge the person or for you to make your own point. We’ve all been at gatherings where someone stands up to ask a question but they really just want to share their own thoughts and opinions.

Brave and curious questions may start with something like “Help me understand…” or “Could you share more about…” It’s a chance for all of us to learn more about others and the experiences that shape them.

We all understand primarily through our experiences. We can read the same data, the same article, watch the same events on the news but have very different understandings and opinions because we’ve had different experiences that shape how we interpret the world around us. Experience is the lens through which we engage and understand the world. We often don’t understand why someone can’t just come to the same conclusion as ourselves when presented with the same evidence. One reason is because we’ve had different experiences which shape how we receive and interpret that evidence. Hearing one another’s stories is one way for us to begin to understand why there might be differences in our hopes, fears, and dreams for our common life together.

I hope to try an Engage: Stories later this summer as the first foray into listening to one another and creating a space for stories. I hope you’ll consider participating by coming and listening or perhaps one day sharing a story of your own.

June 16

The last couple days we’ve gone to Bunratty Castle (Bunratty) and King John’s Castle (Limerick). Both castles were under siege at various times during wars where religion was a major point of conflict. Religious preference and persecution has been a cause of many violent conflicts in Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Bunratty Castle has an interested Pennsylvania connection. When it was under siege in 1646 during the Irish Confederate Wars, the Irish theatre of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (a series of civil wars in the kingdoms of Ireland, England and Scotland) were ruled by Charles I. The conflict had political, religious and ethnic aspects and was fought over governance, land ownership, religious freedom and religious discrimination. The main issues were whether Irish Catholics or British Protestants held the most political power and owned most of the land, and whether Ireland would be a self-governing kingdom under Charles I or subordinate to the parliament in England. It was the most destructive conflict in Irish history and caused 200,000–600,000 deaths from fighting, as well as war-related famine and disease.

William Penn, for whom Pennsylvania is named, was a baby then and he was believed to be in Bunratty Castle during the siege of 1646 because his father commanded the naval forces that controlled the Shannon estuary. His father, also William, had an interesting Naval career. I can’t help but wonder if all the violence and war had an impact on the younger William, which made Quakerism so appealing.

King John’s Castle in Limerick was also under siege during the Irish Confederate Wars and played a key role in driving out the Gaelic chieftains from Ireland.

During the so-called Glorious Revolution (scroll down to read my June 2 post) many Presbyterians fought alongside King William against the Catholics in Ireland, including at the Battle of the Boyne. But soon after that came the Test Acts. The Test Acts were a series of penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and nonconformists like Presbyterians. The underlying principle was that only people taking communion in the established Church of England were eligible for public employment. The Tories in England did not want Presbyterianism to grow. They even got King William to stop giving his promised stipend to Presbyterians after the war.

In Derry, where Presbyterians had helped defend the city, they were suddenly kicked out of the walls. The Catholics inhabited the bogside and the Presbyterians inhabited a similar ghetto on the other side. It was at this time that many Presbyterians began to leave Ireland for America. They were tired of religious persecution and the harm that comes from having an established state religion.

Many of the early framers of the Constitution were Presbyterian and some were from the Derry area (including Charles Thomson who designed the first Presidential Seal of the US). They had been at the wrong end of religious persecution in Ireland and Scotland, and were seeing similar things happening in America with the so-called “Intolerable Acts.” They had lived through it once and weren’t going to do it again. King George went so far as to call what we consider the American Revolution, a “Presbyterian Rebellion.” To be fair, the term Presbyterian was much broader than we think of it today, but it included those who were nonconformists (i.e. not a part of the Church of England and thus subject to persecution.)

The point I’m making is that the founders of the United States had seen the problems of religion being a part of government throughout their lives and in the generations before them. They knew first-hand that religion and politics shouldn’t mix because it almost always leads to oppression and war. We have this myth, perpetuated by many, that the US was founded on faith and is a Christian nation. I think the founders would be appalled at this sentiment. They tried so hard to not tie religion to the government. Many were people of faith, but they didn’t want that faith to seep into the rule of law. They knew that religion can do many good things, but it can also create fanatics and create clear divisions of who is in and who is out. Many had been on the outside before. They wanted the US to be something different because so many had come to America, like William Penn, to escape religious persecution and to find freedom of religion and sometimes freedom from religion.

I think all this is important as we think about reconciliation in America. Our faith is important to us and it should be. It should inform every part of our lives, but we have to remember our faith does not and should not inform everyone else’s lives.

Religion can be a good and beautiful thing and make our world and lives better. But unfortunately, religion has also been a bad and ugly thing making our world and lives worse. History is replete with examples of both.

Religion is like fire in that way. Fire is a wonderful gift and can do some many good things when it’s used properly and in its proper place (stove, fire ring, fireplace). But fire can also destroy when it is used carelessly and not in its proper place. When religion enters into government, it almost always inevitably destroys and burns things down. I think the framers of the constitution knew this because they had lived it. Perhaps some of us have lived it, too. I know some of you have.

One step in reconciliation is acknowledging how religion can unite and can do great things but also acknowledging how religion has divided people in America and also hurt people and oppressed people from the treatment and justification of having enslaved persons to the rights and privileges of women and the LGBTQ+ community. If we can’t acknowledge those truths, we can’t begin to mend what our heritage of faith has broken.

June 15

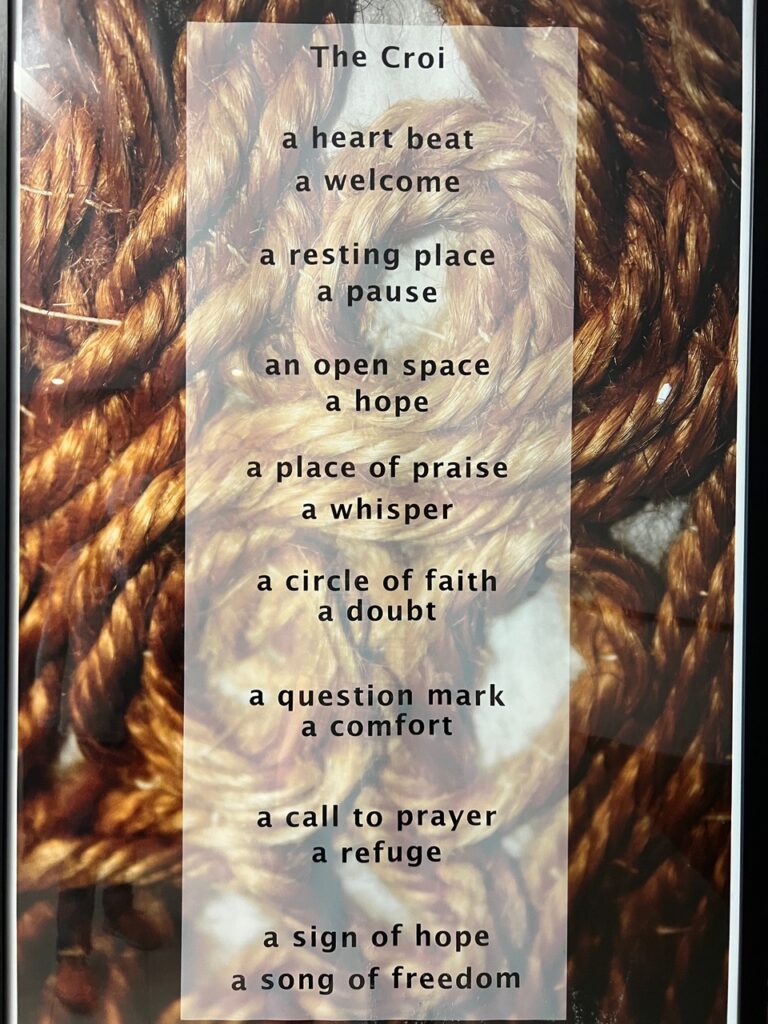

Corrymeela has a rhythm of prayer and reflection twice daily at their Ballycastle Centre. Worship happens in the Croi, which is Irish for heart. I was able to attend one of the morning worship services in this sacred space. The worship time begins with a long period of silent reflection and always ends with these words and this prayer….

Corrymeela was begun by women and men of courage, humanity and faith. We are inspired by their story, the story of the gospels and the story of our world today.

(prayer said in unison)

Courage comes from the heart

and we are always welcomed by God,

the Croí of all being.

We bear witness to our faith,

knowing that we are called

to live lives of courage, love and reconciliation

in the ordinary and extraordinary moments

of each day.

We bear witness, too, to our failures

and our complicity in the fractures of our world.

May we be courageous today.

May we learn today.

May we love today.

Amen.

Members and guests of Corrymeela say this prayer everyday because they know the work of reconciliation takes courage. I see that more and more as I’ve heard stories of people who have take personal and professional risks to reach out across boundaries to enter into relationships with others.

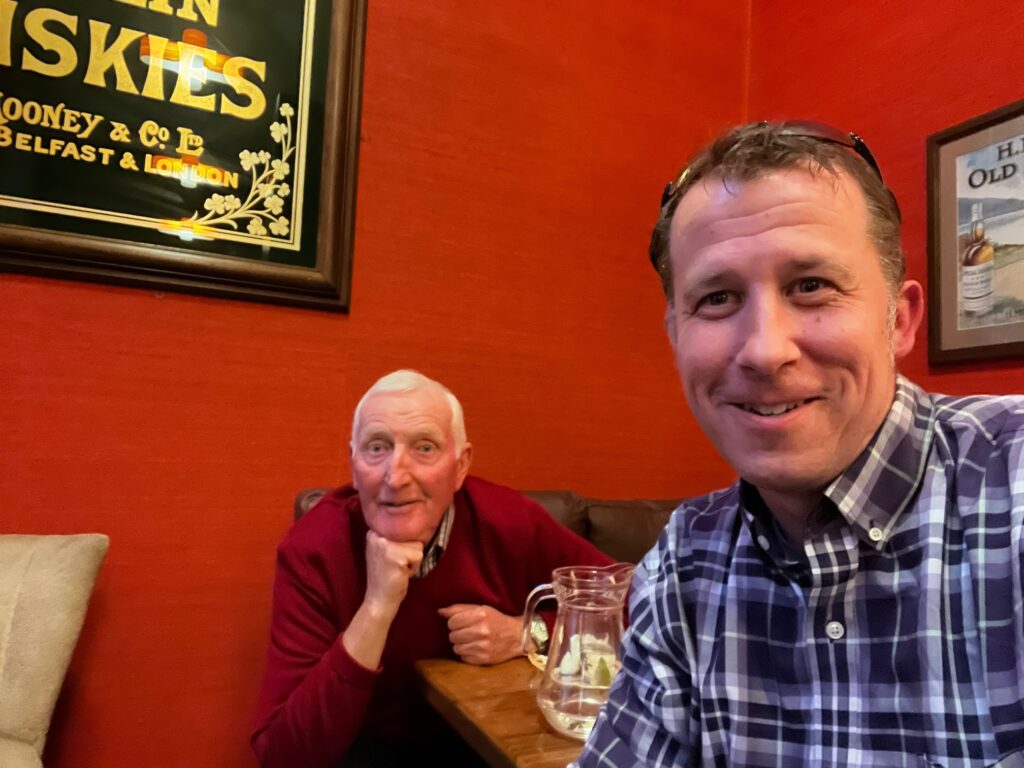

Joe Campbell told me how he had to have cameras installed around his house in the 80s and 90s when he was working with the police force in Belfast. He also had to have anti-bomb protection installed on his car.

Everyone I talked to has lost friends, church members, and had their lives turned upside down in one way or another because they were committed to reconciliation. They’ve been called traitors by their own people for even talking with folks on the other side.

Reconciliation takes courage. It takes courage to move from our comfortable places of belonging in order to find a new space that can be welcoming for you and your enemy. It takes courage to enter into conflict and try to disagree well. It takes courage to try to be in relationships without expectation, agreement, or approval. It takes courage to mend the torn places in the fabric of our society caused by broken and fractured relationships. It takes courage, but courage is something God commands of us. Over and over God tells Joshua to be strong and courageous because God knew he would need both to lead God’s people into the promised land and remain there as God’s people. I’ll be talking more about that in a sermon on July 3.

Until then, I wonder what’s one courageous thing we could do to help mend the tears in the fabric of our society? What’s one courageous thing you could do to be in relationship with someone? Sometimes the most important journeys in our lives take just one moment of courage. What might yours be?

June 14

In January 2023, I’m doing a sermon series on the Book of Ruth based on the book Borders and Belonging by Padraig O’Tuama and Glenn Jordan.

The book of Ruth is about a Moabite woman who crossed a border with her bereft mother-ln-law. By virtue of her devotion and righteousness through trials and tribulations, Ruth brings about a change in the people who will eventually count her as one of their own.

Ruth was not one of them to begin with, though. She was part of a hated group that the Israelites said horrible things about. This woman — who was of the so-called enemy group — ends up judging Israel and turns them into the best of themselves.

Do you know the origin story of the Moabite people? If you do, it’s probably the one told by the Israelites in the book of Genesis. The story goes that the daughters of Lot, after they leave Sodom, get him drunk and take turns sleeping with him: it’s one of those women who becomes the matriarch of Moab. So Moab comes from an incestuous plot. That’s the origin story the Israelites tell about the Moabites. My guess is that is not the story the Moabites tell about themselves.

Have you ever wondered about the origin stories you tell about groups you disagree with? How might the stories you tell about them differ from the stories they tell about themselves? What’s my origin story about THEM?

So Ruth is a Moabite, and for some reason her now-deceased husband had fled Bethlehem (the house of bread) during a famine and went to Moab. Famine often causes migration, as in the case of the Irish migration in the 19th century. With her husband dead, Ruth follows Naomi to Israel. But there was a law against Ruth — against her people, her history, her very body. No Moabite or any of their descendants may enter the assembly of the Lord.

This law from Deuteronomy is because of what YOUR people did to OUR People — back in time when we’ve forgotten who started what, we hold this against you today. Like I said yesterday, we can’t be a prisoner to the past, but we so often are.

It is a repeated story: because of what x did to y; because z started it; because we cannot forget q. It is repeated because it’s powerful, and Ruth is walking into a time-warp, where what was done in the mythologized past is remembered in the real present, and what is remembered is re-membered, so she, in the membership of her own body, is the blank canvas upon which hate-filled histories hang.

It would be comic- or tragic- if it were not so common, so powerful, and so true. We see it acted out against innocent black bodies, men who were abused who act it out on young boys, men who are angry at some woman from their past (often their mother) and abuse the women in their lives. We see it in the cycle of violence in Northern Ireland and in Israel/Palestine.

We do this to each other all the time, and for what seems like good reason. Peoples have treated other peoples like vermin (if we tortured vermin to death in slow, painful, considered ways), and often the perpetrators of this hatred deny this hatred happened, and so the living descendants are bearing witness to truth and life by remembering themselves.

Sometimes we must talk about our remembered pasts, the stories we tell about each other, name the fears and the hatreds or we can end of progressing too far and too quickly down the scale of sectarian danger.

Joseph Liechty and Cecelia Clegg, wrote a book, Moving Beyond Sectarianism: Religion, Conflict and Reconciliation in Northern Ireland. Similar to the Beaufort Scale (which measures wind strength), Liechty and Clegg created a scale to predict the level of sectarian violence. To assess the level of violence, they created a scale based on the way separate sects talked about each other. When sects of people are calm, and at peace, their words about other groups are different than when they are at war. Here is their scale:

Scale of Sectarian Danger

Escalation by words and actions

- We are different, we behave differently

- We are right

- We are right and you are wrong

- You are a less adequate version of what we are

- You are not what you say you are

- We are in fact what you say you are

- What you are doing is evil

- You are so wrong that you forfeit ordinary rights

- You are less than human

- You are evil

- You are demonic

You discover new things when you name your hatreds of peoples to people who are part of those peoples (yea that’s a confusing sentence). When you have to name them to them, I think it slows and maybe even stops the progression, and that’s why we have to be in communication and relationship with each other.

We need to create places where our disagreements will happen in a tone that is wiser and in a tone that is safer. And I think that’s a really helpful place to be because the implication that to agree with each other is what guarantees safety is immediately undermined by every experience of family.

Agreement has rarely been the mandate for people who love each other, and Jesus commands us to love one another, not to agree with one another.

June 13

Today was a travel day from Ballycastle in Northern Ireland to Doolin in the Republic of Ireland. Along the way, the name Colmcille kept coming up. St. Colmcille Church, Colmcille Heritage Center, Glencolmcille, Lough Colmcille. Colmcille is all over Ireland, because he was all over Ireland (and Scotland).

St. Colmcille (or Columba in Latin) is one of Ireland’s three patron saints. The other two are St Brigid and St Patrick. His feast day is June 9, the day he died in the year 597 AD – at the impressive age of 75. Six years ago we were in Iona for his feast day and tradition says if you visit Iona on Colmcille’s Feast day you get a get out of purgatory free card (true story, there’s a sign at Iona and everything so it must be official).

Young Colmcille entered the priesthood at age 20 when he became a pupil at Clonard Abbey, situated on the River Boyne in modern day Co. Meath. We certainly saw many Colmcille churches and other things named after him when we were in the Boyne valley. When a prince cousin gave him some land at Derry, he decided to start his own monastery. The site is just a couple hundred yards from the Derry Presbyterian Church and is just inside the walls overlooking the catholic Bogside.

Colmcille traveled throughout Ireland teaching about Christianity and founded some 30 monasteries in just 10 years. But Colmcille wasn’t a perfect saint. Like the Apostle Paul and like all of us, he had his own issues, mistakes, regrets, and demons. One episode in Colmcille’s life was a 6th century copyright battle. Colmcille and Abbot Finian of Clonary Abbey )where Colmcille studied) got into a disagreement over a psalter. According to one longer version of the story, it was the Vulgate, a Latin translation of the Bible and the first copy of it to reach Ireland, which would make it a pretty appealing piece of literature. Colmcille borrowed the manuscript from Finian–possibly without permission–and secretly copied it with the intention of keeping it for his own use. But Finian said no, that this was theft–illegal copying! He demanded that Colmcille hand over the copy he had made.

Finian took the matter to King Diarmait mac Cerbhiall, the High King of Ireland, for arbitration. Believing he had done nothing wrong in his attempt to spread the word of the church, Colmcille agreed. (It didn’t hurt his expectations that Diarmait was a relative.) Finian’s argument was simple: My book. You can’t copy it. He felt that if anyone was going to copy it that it should be done through certain procedures and certainly not in secret under his own roof.

Colmcille’s response was not all that different from those in favor of less restriction in digital duplication–that the book had not suffered by his copying. “It is not right,” he said, “that the divine words in that book should perish, or that I or any other should be hindered from writing them or reading them or spreading them among the tribes.” In his closing address, he told the court that those who owned the knowledge through books were obligated to spread the knowledge by copying and sharing them. He felt that to not share knowledge was a far greater offense than to copy a book that lost nothing by being copied.

The king ruled in Finian’s favor, famously saying, “To every cow belongs its calf; to every book its copy.” In other words, every copy of a book belonged to the owner of the original book. Colmcille felt dishonored. Next Colmcille harbored a fugitive from Diarmait and then led troops in the Battle of Cúl Dreimhne. The result was the death of 3,000 people, and Colmcille’s exile. Then Colmcille sailed to Scotland and founded the monastery at Iona. He vowed to never set foot in Ireland or see it again as penance. But in 575 Colmcille was persuaded to visit Ireland to mediate a dispute between the high king and the league of poets. Insisting on remaining faithful to the terms of his vow, he travelled blindfolded and strapped lumps of Scottish sod to his sandals so he wouldn’t see or step foot on Ireland.

It is believed the Book of Kells was written in Iona and eventually taken to Kells Ireland to protect the book from Vikings as Colmcille’s community outlived him and eventually moved back to Ireland.

Colmcille is an important figure in Celtic Christianity for both Ireland and Scotland. He did some great things, but he also did some regrettable things. This is why I’m telling his story. The bad he did doesn’t render the good moot, and the good doesn’t just wash away the bad. We don’t just cancel Colmcille and re-name all the churches and communities because of his mistakes, and his mistakes weren’t minor. Three thousand people were dead because of his conflicts. On the other hand, we shouldn’t pretend he is a larger-than-life near perfect saint.

We all are mixtures of sinner and saint, and if each of us are judged by our worst days or when we had to make really tough decisions that inevitably hurt others, we’d all be considered pretty awful.

With every historical figure and every one of the neighbors we’re called to live with today, there is something we are going to have to forgive in their life in order to receive a gift they have the ability to give. Some of the best artists led really messed up lives, and we may have to forgive that to see the beauty they offer. Some scientific breakthroughs came from men and women who did some pretty awful things. There’s something to forgive in everyone and there’s a gift everyone can offer the world. We don’t reject the gift because of the past and we don’t erase the past because of the gift.

Sometimes we have to learn to let the past be the past, discern what we can learn from it, and then move forward.

Many of you know I have “Four Simple Rules” for living life together: Don’t be a jerk, Don’t Make it Weird, Don’t Make it about You, and Don’t Freak Out. I think I’m adding a fifth: Don’t be a Prisoner to the Past.

The past is important. It is a teacher and it forms us. It cannot and should not be forgotten, but it also can’t dictate our future completely. We all have past hurts and traumas and grievances that can hold us hostage. We all have mistakes and poor choices that could define us forever if we let them, or if other people hold them over us forever. But we have to find ways to move on to better days and better choices. We must do that for ourselves, and for our loved ones, and yes, even for our enemies.

No one is perfect, not even St. Colmcille, but we all have a gift to give the world despite all our flaws. Let’s make sure we give it, and let’s give others a chance to give theirs and be ready to accept it when they do.

June 12

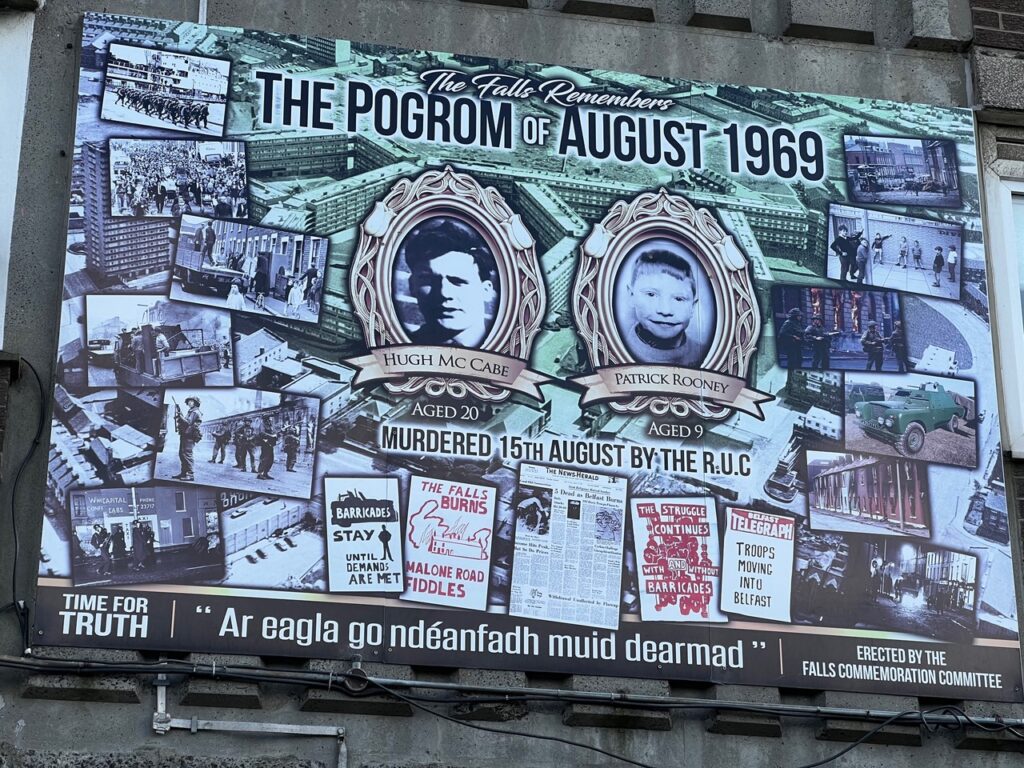

When I was in Belfast, I took a Black Cab tour through some of the sectarian neighborhoods that were torn apart by violence from the 1970s-90s. But this was no ordinary tour: instead of one cab, I took two cabs. The first half of my tour was with an Irish Republican, and the second half was with a British Loyalist. Instead of an objective look at the Troubles, I wanted to hear raw, honest, partisan perspectives.

A few interesting facts and statistics stood out to me. Belfast was the largest militarized zone outside Vietnam in the 70s. Still today, mixed marriages between Loyalists and Republicans are only 10% of all marriages. The re-homing of Irish Republicans was the biggest forced migration in Europe since WWII. The Peace wall that was erected in Belfast is bigger than the Berlin wall was. Many of the older community members affected in Belfast continue to take anti-anxiety medication and salves because of the trauma they lived through. The youth suicide rate is also extremely high, showing the results of trans-generational trauma because the fight or flight instinct was on for decades.

So much of what I saw and heard felt so familiar to the historical and current situation and rhetoric of our country over a myriad of issues. In some ways, the Irish conflict is easier to identify because the lines are clearly drawn between the two sides. You know who is who. In the US it is very different. We have religious conflict, political conflict, social conflict, and cultural conflict. There isn’t a clear “other” we know is our enemy. There are clear dividing lines, but we see the results of deep divisions every day.

The conflict, like most historic conflicts, is complicated. Each side has very legitimate grievances. Each side has trauma and pain and can lay plenty of blame at the others’ feet. I’m often struck when people can’t understand why someone would protest or riot or even commit acts of horrendous violence, because I can understand it. When you hear the stories of hopelessness, of oppression, of violence, you can begin to understand rage and the helplessness.

For example, the Irish people were systematically removed from their homes and jobs by British Loyalists. Then the Catholic Irish couldn’t get anything but the worst paying jobs so they couldn’t afford homes. They were moved into ghettos and had to rent from Protestants. Then laws changed, saying you had to pay property taxes to vote, but the Irish now didn’t own property so couldn’t vote. The landlords got to vote for them, so one British Loyalist could own several properties in Catholic neighborhoods and cast their votes. And then came the gerrymandering making the few Irish Republicans that could vote have no impact whatsoever. There was no political recourse for Irish Republicans. They’ve lost their homes and their jobs. They’ve lost the ability to participate in government, and they’re persecuted by a police force that’s 95% Protestant. They’ve tried the legal approach again and again and it hasn’t worked. What’s the definition of insanity? And then when innocent Irish are murdered by police, it all reaches a boiling point. Can you imagine a point when you may commit violence yourself, or at least condone or support those who do it on your behalf? I think we all can if we have a small bit of imagination and we have a deep love and commitment to anything, because when that is threatened or hurt, we will act.

Of course, that’s just a bit about the Irish Republican side. There’s another side of the story, too. What struck me about the dual cab tour is that while I was listening to each person share their story of pain and trauma and outrage, I felt empathy to them. I felt angry for them. I felt they had been wronged. But then, I hear the other side and I feel the same way. This is the power of storytelling and narrative.

I was watching a show called Dynasties, about families of wild animals in Africa. When I was watching a series about lions, I empathized with the lions. I wanted the lioness to kill the zebra to feed her starving cubs. I wanted the zebra to die so the lions could live because I was invested in their story. Then the next series was on a zebra family from the same area, and I found myself hoping the mother zebra would get a good kick in on the lion and kill it so the zebra could escape and protect her child. We tend to support the stories we hear, which is why it’s so important we hear as many stories as we can. It’s why so many want schools to be more diverse in curriculum perspectives and make sure libraries have stories from various points of view representing people of various races, cultures, abilities, and identities. If we limit the narratives we hear to one dominant point of view, we tend to believe that’s the reality. We tend to side with that point of view and can’t understand why others don’t see the world the way we do. It may be because they are hearing and living the stories we aren’t.

One important thing I heard from both men giving the tours is that they don’t want to go back to the way things were. They know one side is 100% Irish and nothing will change that. The other side is 100% British and nothing will change that. They know they cannot change each other’s identities, but both emphasized the need to listen to each other and find ways to live together because neither wanted anyone else to die over this conflict. They know they have to talk to each other in order to live together and move forward, but sadly the communities are still very divided (mostly separate schools, recreation leagues, etc but it is slowly changing).

Both sides have trauma and painful pasts and it’s hard to give those up. It can sometimes feel like a betrayal of those who died or were murdered to move forward with those who caused the trauma, but the only other choice is to continue the cycle of violence. At some point, the past has to be left in the past. It doesn’t mean we never remember, it doesn’t mean we don’t learn from the past, but it does mean the past pain cannot dictate our future. What some did in the past may be regrettable and even horrendous, but some of those people are now leading the way of peace in the future.

The British Loyalist commented that he couldn’t possibly trust an elected government made up of past IRA terrorists. That’s understandable, yet I pressed him on trying to understand why those leaders did what they did and how they might have changed now because another way forward is possible. As Rev. David Latimer said, the Apostle Paul was a terrorist for all intents and purposes, but we don’t hold his past against him. In the US we are having problems letting go of the past. We are condemning people’s futures for past mistakes and past bad actions. Yes, there often has to be consequences, but sometimes we have to move forward and find ways to live together. The other choice is no real choice at all.

The Irish know this because they have lived through something so horrible that no one wants to go back to it. I don’t think we’ve come to that point in the US. We think we can defeat the other side or change them or legislate them into submission; but it never works. Ireland is just one example. We have to find ways to live together now in peace before we are brutalized by the divisive rhetoric and the violence and the constant fighting through the cable news and the governments and the courts.

We can’t afford to wait. We can’t wait until every thing is just and everyone says they are sorry and the situation is just right for peace. We have to make peace even when it’s hard, even when it isn’t perfect. We have to make peace and live together even when we don’t agree and don’t approve and don’t even like each other. We have to find ways to hear each other’s stories, to talk, and to make space for the diverse ways of being American and the multitude of hopes, dreams, and needs our country produces and provides.

June 11

Today I met Jenny Meegan in Belfast. Jenny is an ordained Methodist minister and longtime member of the Corrymeela community. She moved to Belfast from England at the beginning of the Troubles in the late 60’s and has been active in peace work ever since, especially in prisons with political prisoners.

I asked Jenny how she would define reconciliation. She says the word has become professionalized in many ways, but she goes back to the simple definition of forming relationships with people, listening and sharing stories, and meeting people where they are without expecting them to change. Reconciliation often happens by accident, but you have to be open to it and the possibilities of new relationships.

Reconciliation can’t be forced or contrived. Relationships need to be natural, but space needs to be made in our lives for people of difference. We need to make space to hear each other’s stories without an expectation of change or approval. It’s okay to hear someone and be in relationship with them, to love them and work for their well-being without approving of them.

As a Methodist, Jenny is lamenting the coming split in her church over LGTBQ+ issues. Almost every major denomination has split over the issue in the last few decades. Jenny mentioned the new book by Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, on reconciliation. He defines it as the art of disagreeing well. The church has not disagreed well. We put beliefs above relationships and those beliefs are constantly drawing new lines and barriers between us and others. It’s understandable, though. When one side believes strongly that something is wrong and they cannot condone it, and another side thinks something is absolutely right and God commands it, these strong beliefs don’t have much flexibility. We don’t want a wishy-washy faith, but we also don’t want to constantly show the world that the best way to handle disagreement is to cut ourselves off from one another and split.

The Bible tells the story of God inviting humanity into a new way to live together, a better way. But we don’t talk much about that invitation. We focus on eternal life, and our own forgiveness, and the person of Jesus. We don’t spend that much time talking about what Jesus talked about and this invitation to live in a new way — the Kingdom (and/or kin-dom) of heaven way. Perhaps we don’t talk about it because it’s hard and we don’t live it.

One of the Great Ends of the church is to be a provisional representation of the Kingdom of Heaven to the world, but what are we showing the world? We don’t take the lead on reconciliation and we don’t live together all that well. Churches are constantly splitting every generation over different beliefs. We don’t disagree well, so how can the church help heal society when we can’t even heal our churches and denominations?

Part of reconciliation is learning to prioritize relationships and being able to have relationships without agreement or approval. We’ve been taught for so long we have to approve and agree to be good friends. Both the left and the right now want to cancel people whom they disagree with and they pressure individuals to cut ties with those who do not hold woke enough, patriotic enough, holy enough, conservative enough, liberal enough, or moral enough views. The church has been just as guilty of this.

I remember when the church I was ordained in and was a member of in high school left the PCUSA. They said they couldn’t associate with people who were as ungodly as the PCUSA. They compared it to being sullied by something dirty. I grew up in that church, helped lead youth group in that church, learned in that church, and was ordained for ministry by that church, but apparently for them to associate with me now would be ungodly. And relationships are lost.

We do it all the time. We cut off relationships over beliefs and the world and our lives are the worst for it. We need to learn the art of disagreeing well. We need to learn that relationships don’t require agreement. We need to stay in the room with difference. We need to listen more and stop expecting everyone to change and conform to our view of the world. Perhaps if we listened more, we’d learn why they see the world differently, and it may just make sense even if we never agree.

June 10

When I visited Corrymeela I had the opportunity to meet with Derick Wilson, a former leader and active member of the community. Derick showed me around the campus and explained more of Corrymeela’s history and mission. We worshiped in the Croi and then had tea and talked.

As with all my conversations, I asked Derick to define reconciliation. He said reconciliation is the overcoming of enmity and hostility between people but it’s also about the relationships and structures through which we are at ease with one another. Reconciliation is based upon our relationships and the structures that maintain those relationships. It’s the central message of the gospel, but churches have too often seen it as peripheral.

There’s been a constant theme in all my conversations that churches have been reluctant to engage in reconciliation. Perhaps because it’s hard and it’s risky and it’s complicated. Too often we’d rather just define ourselves by our beliefs and form like-minded community. That’s easy and comfortable and allows us to set ourselves apart.

Derick lamented that beliefs and positions are becoming more important that relationships, which is causing a rise in sectarianism around the world and in the US (sectarianism is simply excessive to a particular sect or party, especially in religion or politics). Community should be welcoming, embracing, and expansive, but often community now is used in a more narrow and exclusive sense. Beliefs are often used as a shibboleth, or litmus test, for entrance into a community. Our beliefs are not only defining communities but building walls around them and barriers not only to entry but to relationship and dialogue.

But the stories of the Bible are a continuing invitation to live differently with one another. It presents a new and different vision of life together. Derick believes the Bible unveils the violence in human history and it culminates in the crucifixion of Jesus. Humans get locked into securing their own way through violence and the cross unmasks that. History in large part is the story of how one group or another seeks its own advantage and way through violence.

And then all dominant cultures try to exist without acknowledging the violence at its root, whether that’s the Roman, British, or American empire, or toxic masculinity, or white supremacy, or dominant religions whether Christianity, Islam, or Judaism.

There are possibilities for us to live in new ways together with different people without violence, but Derick laments that churches often hide that. They, and we, aren’t highlighting that invitation in the Bible. We focus so much on heaven that we are missing the salvation we need as we live together right here and now. Jesus talked much more about life together on earth and relationships than he did about eternal life or heaven.

In order to live in a new society that doesn’t secure its own way through violence, we need schools that don’t tolerate bullying, civil services that promote peace and justice, politicians who listen to those who hold different ideas and ideals and will work for the common good with them, and faith communities who will risk in order to reconcile and become inclusive communities.

Sadly, religion often focuses on how we are right and they are wrong. We have our beliefs and we must do what we have to do to protect and preserve those. This has often led to war, prejudice, exclusion, and broken relationships. Jesus focuses much more on right living with our neighbor than right belief, but we’ve prioritized it the other way. Religion has therefore often exacerbated difference and then used it to justify violence to maintain power, position, and privilege through the centuries.

When religion is just a code of beliefs it’s something to fight about. Derick argues religion should be less about a people of beliefs and more about a people of relationships. He argues we only need faith the size of a mustard seed to be big enough, or beliefs the size of a mustard seed to create the habitat for every sort of people to be in relationship together (if you remember the parable of the mustard seed).

Groups with beliefs (whether religious, political, cultural, etc) tend to find ways to justify violence, deny historic violence, and we now are seeing display a willingness to commit violence.mThis is what is beginning to happen in Ireland since Brexit and we’ve seen in the US over issues of racism, justice, abortion rights, toxic masculinity, and more.

Derick argues we must find ways to be together without rivalry and that’s done with relationships of trust and openness. He says we have to put relationships before beliefs — even sacred beliefs — because we’ll never be content with beliefs. We can never believe well enough or be perfect enough, and there will always be those who don’t measure up to our beliefs that we can then justify excluding and that often leads to dehumanization, oppression, and violence. It happened in Ireland and so many other places throughout history.

We talked about so much more but that’s a snippet of our conversation. I’m struck by a quote on the roof over the exit to one of the buildings at Corrymeela. It’s something their founder often said, so it can be read as you leave the space of meeting to go out into the world: “Go and see what needs to be done.”

I’m gaining a clearer picture of what needs to be done, at least for me. That’s the message Jesus gives us again and again. “Go and see what needs to be done.” Leave your comfortable places of belonging, leave your closed off communities of exclusive belief, leave your old ideas, and go see what needs to be done: there is so much work to do. But there’s hope and an invitation from God to live in a new way together. What can you and I do, what needs to be done, to begin living in that way together?

JUNE 9

Today I had the pleasure of meeting with Rev. David Latimer who retired a few years ago after serving over 30 years at First Derry Presbyterian Church.

Rev. Latimer may be retired but he continues to be active in peace work in Derry. You can read about a recent event he participated in.

David struck up an unlikely friendship with the former provisional IRA leader of Derry, and eventual Deputy First Minister of N. Ireland, Martin McGuiness. It was not a universally popular move in the town or in the church. Some questioned how he could befriend someone who had done committed such acts of violence. There’s of course a lot we could unpack about violence done in revolutions, when under threat, or when oppressed, but David pointed out the example of the Apostle Paul. He certainly was not a man of clean hands. He was probably the ring-leader when Stephen was stoned to death, and yet we venerate him. David shared a quote by Rev. Jesse Jackson he thought was fitting for his context and really for every context, “None of our hands are all together clean or hearts all together pure.”

It took courage for David to connect with Martin and continue a friendship in the hopes of pursuing reconciliation and peace. It was hard, but there were moments that made all the risk-taking and abuse and angry letters worth it. He shared how he had asked Martin to speak at his retirement celebration, and a man from his congregation whose son had been killed by the IRA came up to Martin and shook his hand and said he spoke well. That one interaction was huge for both individuals, but was symbolic of the potential for reconciliation.

Reconciliation cannot, and will not, be achieved without risk by all those involved. Speaking about this fact, David shared a favorite quote he attributed to a former ambassador to West Germany. “Even the turtle, to move forward, has to stick out its neck.”

We lamented the fact that the church has never been keen at taking risks even though the church follows a risk-taking, trouble-making savior. Churches are often stuck in the fear of alienated the community or part of its membership so what the world needs the church to do is so rarely done. Northern Ireland needed churches to lead in reconciliation, but they rarely did. America needs churches to help bridge divides, but so often religious belief causes divides or strengthens them.

The church has to be willing to risk something in order to be peacemakers and reconcilers. Reconciliation is at the heart of the Gospel. Jesus invites us into a new way of living, but we so rarely take it. We want to continue our own way and we invite Jesus to join us rather than leave how we live to join Jesus.

David shared the idea that God doesn’t care if we cross an ocean, but is tremendously excited when we cross the street to be a good neighbor. What boundaries can we and do we need to cross in order to be better neighbors? That’s what I want to focus on doing when I return to the States. I want to focus less on beliefs and more on relationships. I want to sit down for coffee with people I profoundly disagree with or have seemingly little in common with, and just talk and listen without an agenda and without the hope of changing someone. I want to be a better neighbor, and that means I will have to stick my neck out. I wonder: what it would look like for churches to collectively stick out our necks together in the hope of reconciliation, peace, and a better life together?

June 8

When I was a child in Spartanburg, SC my family participating in the Irish Children’s Program for several years. For six weeks in the summer a child from Northern Ireland lived with us and spent the summer away from the chaos of life at home in the early 90’s with host families and with other kids from home who were both Republican and Loyalist. The first two kids who stayed with us were closer in age to my older sister, but the last kid was a boy my age named Marc.

Today, I had the opportunity to connect with Marc as we took a boat tour along the Antrim coast. Four years ago when I came to Northern Ireland for a week I was able to see Marc for the first time since he left our home in the early 90s. I was thrilled to connect with him again.

I’ve always wondered if the Irish Children’s Program did any good. Did it change attitudes and lives? Did it help with reconciliation in Northern Ireland? I posed these questions to Marc.

Marc says he still talks about the experiences he had when he stayed with our family. Not only did he get to come to South Carolina, but while he was with us we traveled to Williamsburg Virginia and stopped at HersheyPark (Marc still remembers the chocolate factory ride and getting a piece of chocolate at the end) as we traveled to our cabin in upstate New York. On the way home we went to New York City. Marc affirms it was absolutely a fun holiday full of once-in-a-lifetime experiences, and if that’s all it was, I think that would still be enough. Kids living in Belfast were under constant threat, and that takes its toll. I think they all needed a break from the pressure cooker they lived in, always wondering when the next bomb would go off. I imagine some kids in the US are starting to feel that way about mass shootings. Marc actually made the point that he looks at the US as much more dangerous than Northern Ireland.

I asked Marc if the relationships he made with the Catholic kids lasted when he returned home. He admitted that it was hard. When they returned home they went back to their separate schools and separate neighborhoods and lives. It’s a bit like the movie The Breakfast Club. The students bonded over a shared experience, but knew that special time wouldn’t last. But there were opportunities through the YMCA to occasionally get together with the other students.

The experience probably humanized “the other” for Marc and the other students who participated. Experience precedes understanding, and the kids who came to the US had the opportunity to experience difference, and perhaps over time had a bit more understanding. We can’t understand the other, the enemy, the opponent, the neighbor without experiencing them and hearing their story and sharing life together. Sometimes just a simple meal is a good enough starting point.

As we approached the harbor, Marc said he’d been thinking about the questions I asked. He hadn’t thought about it much before, but when he returned home he began looking for friends and relationships beyond his neighborhood. It’s not that he abandoned those friends, but he wanted more. He wanted a bigger life beyond the confines of where he grew up and he credits a lot of that to his opportunity in the US. He saw the same thing in other kids from his area that participated in the program, too.

I said yesterday that one thing we all can do for reconciliation is to lead bigger lives. I give a lot of credit to Marc, and his parents, for the courage to come over to the US and stay with a strange family for six weeks. Reconciliation takes courage. Leading a bigger life takes courage because it means being open to new experiences, new people, new hopes and dreams, and new ideas. And when we face all that newness there is a real possibility of change happening. That can be a scary thing, but it’s a beautiful thing.

In the summer of 2020 I started asking a lot of questions on Facebook as the country wrestled with racial injustice. I asked questions like “when did you first have a black teacher?” Many people said they never did. “When did you last eat in the home of someone of a different religion or race?” “When did you last visit a country that was not predominantly white?” I asked a series of these questions to get people, myself included, to examine how big our lives are. We often stay within our bubbles. It’s easy and comfortable, but it doesn’t change us or the world. We need to have the courage to go bigger and broader. Courage is key to reconciliation and I’ll talk more about that soon. Our lives are so much bigger than our hometowns, our churches, our friend circles, our religion, our race, our political party, and our nation, but we often don’t take advantage of how big and beautiful this world really is.

A couple years ago at a Rotary meeting in Hershey, the President of Dickinson College addressed the group. When asked what was the one thing we could do for kids to help them be better citizens of the world, she said “travel.” Experience precedes understanding and travel is full of new experiences and it broadens and enlarges our worldviews, our experiences, our hopes, and our beliefs about what is possible. I’m thankful Marc and so many other kids from Northern Ireland had the opportunity to travel to the US and I’m thankful I have the opportunity to travel with my kids today. What makes it even more special is for my son and daughter to meet people like Marc.

So how can you make your life bigger? Travel is one answer, but there are many more ways right where we live. It will take courage and a bit of vulnerability, but I believe a bigger life is always better.

June 7

Today I took a black cab tour of Belfast that shared perspectives on the conflict from two point of views. I was with a Republican in a Taxi for the first half, then changed taxis to continue the tour with a Loyalist. I heard and witnessed a lot and it may take a few days to let it all settle, but I was drawing so many comparisons to what is happening in the US.

After my tour I met Joe Campbell for dinner. Joe is a member of the Corrymeela Community and has been working as a reconciler in Northern Ireland since the early 80s. One of his main areas of work was with the police force. You can read an old article about Joe’s work in Ireland. I learned a lot from Joe’s story that I’ll be thinking about for a long time, but tonight I’m really thinking about our conversation about the church’s role in reconciliation.

I asked Joe how he would define reconciliation. He responded that reconciliation is a journey that takes courage and requires a willingness to let go of old hurts and both accept and give forgiveness. Joe also said that reconciliation begins with me and not the other person.

Forgiveness is hard. Since I visited Dunluce castle today (C.S. Lewis’s inspiration for the castle of Cair Paravel in the Chronicles of Narnia), I thought a Lewis quote would be appropriate. Lewis said, “Everyone thinks forgiveness is a great idea until they have someone to forgive.”

Joe lamented that there was no vision for reconciliation in the church, Protestant or Catholic, for many years during the Troubles. The church was really late to enter into reconciliation work and often it only participated when it was funded by some outside group. Very few churches and faith groups, even today, invest in reconciliation work.

We shouldn’t let that be the case in the U.S. The church needs to be setting the agenda for reconciliation, not waiting for it to slowly filter down to us. The church needs to lead the way in society for bridging divides and creating safe spaces for conversation and learning to live together despite profound differences. The church needs to model life together, not be a place that furthers divides. Unfortunately, that was often the case in Ireland, and is often the case in the U.S.

So the question I’m really pondering is, “Does faith make a difference in this broken society and if so what does it do?” Perhaps you can consider your own answer to this question.

I’ve learned there’s one thing we can all do for reconciliation: make ourselves bigger, broader, and wider. In other words, to enlarge our circle of friends to include different kinds of people, to broaden our minds and hearts to new ideas and people, to widen our hearts to be gracious and more forgiving and understanding of difference. We need bigger attitudes, bigger dreams, bigger hearts, bigger tables, bigger circles of life together. Draw the circle wide, draw it wider still.

June 6

Today was a travel day from the Boyne Valley in Ireland to Ballycastle in Northern Ireland. On the way we stopped to see celtic high crosses in Monasterboice. They are considered to be the finest examples of early Irish art and celtic crosses to be found today.

I’m in Ballycastle to visit the Corrymeela community. My sabbatical is focusing on the power of stories in the work of reconciliation, so it’s fitting to start with the story of Ray Davey.

Ray Davey was a Presbyterian minister born in Belfast in 1915, back when the land was still just called Ireland, and Europe had just entered into war the prior year. Ray grew up in World War I and, in World War II, he went as a volunteer padré with the YMCA to a respite camp in North Africa. There, he was captured and held in many prisoner of war camps.

He writes about the inhumanity and the humanity he saw in those camps. He saw men whose bodies gave up on them. Ray kept men alive with time and company. Throughout his POW experience he came to the view that while food was essential to live, hope and some wider sense of communal belonging was essential to survival and mental well-being. The last camp he was kept in was outside Dresden. His liberation came with the annihilation of that city. Some cheered. He wondered how to be glad. “When your enemy falls, do not rejoice,” someone wrote once. Whoever wrote that must have known rejoicing, either because their enemy fell or they were the enemy of someone, and they fell, and they saw their opponent’s joy. Ray wasn’t sure what to do. He was free now. Or soon to be. But 25,000 people were dead in Dresden.

Ray came back to an Ireland still in the first quarter century of its partition, and saw that enemies were still stirring there: some loved the border, some hated it. Some were spoiling for a fight and rejoiced at the possibility of fallen enemies. He became chaplain of Queen’s University in Belfast and began groups where the living could encounter each other before they knocked the living daylights out of each other. These experiments in community were with students who didn’t know each other, they were on the edges of religion.

Ray made little communities of people wherever he went: prisoner of war camps; chaplaincies; summer trips; Sunday evenings at his house. In the 1950’s he established German / Northern Irish Student exchange programs involving home stays in both countries -something totally ‘out of the box’ in terms of building peace between countries previously at war.

In 1965 he heard of a place for sale 50 miles north of Belfast, a few fields with a rickety house and a view over the sea across to Scotland. The civil rights movement in Ireland was in full swing just as it was in the US. Some believed that marching would work. Others itched for blood. There was talk of strikes and bombs and guns and military command. What was needed, he thought, was a place for encounter between the living, so that enemies don’t need to come back in dreams. He raised the money in three weeks and bought the house with the view on the fields called Corrymeela.

The Corrymeela Community was named by the land and began its mission to transform division through human encounter. Corrymeela became known as a place of reconciliation. It is a place for practical programs of reconciling work bringing children, young people and adults from diverse backgrounds to meet together and work practically to establish and sustain programs that promote a more open, diverse and shared society.

Corrymeela is a space owned by a community of Catholics and Protestants; a shared space open to all in the midst of this borderland where so many community spaces are still owned by one tradition or another. Corrymeela began because of Ray’s story but it continues because of the stories of its members. I am looking forward to meeting some of its leaders and community members and hearing those stories and learning from them so I can make my own story one of peacemaking, healing, hope, and reconciliation.

June 5

Today I visited Glendalough, which is a valley with two lakes and the ruins of a monastic city. St. Kevin lived as a hermit there in the 6th century before others joined him. Eventually the city was created, and it gained in wealth and importance until the 13th century.

I took the 30-minute walk through the woods at the base of a mountain to the upper lake. It was raining but that did not deter me. Despite the rain and fog, I took in the beauty and peace of the place. It’s one of those thin places where you feel closest to what is holy. It was a sacred space and I enjoyed just being still and quiet there. We need sacred spaces

When I met with Jin Kim, we talked about what was required to get people to meet with those they may consider enemies and share honest stories and hear honest stories with grace. He talked about the need for sacred spaces. A conversation that may not work at city hall may work in a place like Glendalough or Corrymeela or maybe even a church trusted by the community. We need sacred spaces where we can let down our guard and honestly talk with one another even if it hurts, knowing we can be healed in and by and through that sacred space.

June 4

Today I went to the Irish Heritage Park in Wexford, which focuses on pre-history Ireland, the early Christian period, and the period of Viking invasion. Then we went to New Ross to visit the Dunbrody Famine ship, a re-construction of a real ship that sailed poor Irish who were forced to emigrate from the country due to hunger and their landlords wanting land for themselves.

Conflict in Ireland between Protestants and Catholics/Unionists and Republicans/Irish and English is the result of hundreds of years of British and Irish identity rubbing up against one another often causing points of severe friction like the revolution of 1688 and what we typically call the potato famine of 1845-47. In Ireland it is known as the great hunger because there wasn’t really a famine. There was plenty of food… just not for the Irish.

70% of the corn the English ate and 60% of the beef came from Ireland. There was plenty of food but imperial England claimed it. Men died of hunger packing food onto ships to be sent away. Before the hunger there were approximately nine million people in Ireland. During the hunger, two million people emigrated and one million people died, leaving a population of about six million. The population of Ireland is still at about 6 million people. It has never recovered.

Poor Irish were often forced to leave their homes and move to America. Their landlords paid their passage (in steerage) and then could reclaim the land to use as pasture. The journey to America was extremely dangerous. The famine ships were often called coffin ships because so many died on the voyage. Families would have to spend 23 hours a day in the dark confines below deck living on meager rations packed into bunks like sardines. But they had no choice. We often think most Europeans who came to America chose to come to seek a better life, but more often than not they had little or no choice.

The Great Hunger was exacerbated by the potato blight but was really a direct result of British imperialism. Most of the food Ireland produced went to England. All the wood went to England, too, so the ships that sailed the Irish to America had to be built elsewhere. The Dunbrody was built by an Irishman living in Quebec. Imperialism often results in the diminishment and abuse of a colony for the advantage of the colonizing country. It has happened in Africa, India, Ireland, and even America. Those in power are very aware of what they are doing to indigenous people of colonized territories, but often the average person has no clue. We rarely look too deeply into how we get the luxuries and resources we use every day.

In the Sermon on the Mount Jesus says that if we are presenting a gift at the altar and but a brother or sister has something against us, we should stop and go be reconciled to our brother and sister and then come back and present our gift to God. It’s hard enough when we know someone has something against us, it’s even harder when we are not aware or choose to be ignorant of the problems.

I doubt most English in the 19th century really realized they were starving the Irish, but then they probably didn’t ask where their beef and corn came from and at what cost. Someone always pays… for the food, the energy, the land, the wood, the stone… it’s just easier if we don’t have to know. This is one of the problems of imperialism, it can all happen so far away we can be ignorant. But it’s harder now because the world is flat and information is a click away. We can find out about where our food comes from, and who makes our clothes, and where we get our diamonds, and our fuel.

Which makes me wonder if I’ve ever benefitted at the expense of someone else. Have others starved so I could have more than enough? The answer is most certainly yes. Who do I need to go and be reconciled to because of how I have lived, even if it wasn’t intentional? Who has paid for my abundance and luxury? I need to go be reconciled to them. I need to help make things right. I can’t change the past, but perhaps I can alter the future for the better. And then, and only then, should I present my gift at the altar.

June 3

Today I had the privilege of meeting with Dr. Dong Jin Kim, a senior research fellow in peace and reconciliation studies at Trinity College and a member of the Corrymeela Community. His research and work focuses on reciprocal empowerment.

Dr. Kim worked with a few other members of the Corrymeela Community to create a new 10-module resource called “Nurturing Hope.” I hope to use the resource at Derry in the future.

I had a truly fascinating and enlightening conversation with Dr. Kim as we talked about his work and my hope to harness the power of personal stories to facilitate reconciliation.

I’ve been asked by several church members, “What is reconciliation?” and I will be asking those I meet with for their definitions.

Dr. Kim says, “Reconciliation is building relationship between people who were oppressed because of the conflict structure so they can achieve peace with justice.”

One of the most interesting takeaways from our conversation was the idea of ontological anxiety (or anxiety about our identity and belonging) and how those in power will use this fear and anxiety to manipulate populations who have more in common than they realize and aren’t really each other’s enemies (but they are set up to be).

I’ll be thinking and writing more about the consequences of ontological anxiety in the future and how it has been at work in Ireland and America.

JUNE 2

I’m in Ireland to fill my pockets, heart, and mind with stories and experiences of a place and people who have found a way to work toward peace and reconciliation after generations of division, trauma, and violence. Today I went to the site of the Battle of the Boyne, a battle fought between Protestants and Catholics to determine who would sit on the English throne.

Trouble between the English and Irish goes back hundreds of years, but a significant year for conflict was 1688. This was the year of what some historians called the Glorious Revolution. I remember a college British history class calling it the Bloodless Revolution. The class failed to mention all the actual bloodshed, a lot of which was on Irish soil. The parties who gained the most from the removal of James II and the installation of William and Mary wrote the histories we have heard. History is basically a collection of stories intertwined and compiled by individuals, groups and cultures, but someone is always choosing which stories are told.

For the Irish the regime change in 1688 was neither Glorious or Bloodless, but it wasn’t until the second half of the 20th century that the English began to be aware of that alternative narrative of 1688. Every year on July 12 the victory of the Protestant William over the Catholic James is celebrated in Ireland by Protestants, especially the Orange Society. During the Troubles, these celebrations and parades were often the scene of violence committed by both sides. For the Protestants it was a day they often went a bit overboard celebrating continued Protestant English rules in Northern Ireland. For Catholics it felt like a yearly rehearsal of a traumatic past in which they were reminded of all they lost.

In the 90s and more recently, the English have begun to recognize and lift up the counter narratives of 1688 that don’t define the events as Glorious, but as painful. This has helped heal old wounds and forge a path of peace. Sometimes we need our pain heard and stories retold.

One of the first steps we can take toward reconciling with difference is to critically examine our histories and the stories we choose to tell and those we have willfully or unknowingly ignored or suppressed. We then need to seek out the Counter (or alternative narratives) and make space for those in our own telling and understanding of history.

For instance, George Washington is considered an American hero and a great man. There are ample stories to support that view of Washington, and I certainly hold that view. But can we also see room for the stories of how he owned slaves, separated families, and committed atrocities against fellow human beings that we would denounce today? Listening and making space for those stories doesn’t negate all the good Washington did, nor his many great attributes and acts, but it does help us understand that he was more of a tyrant to dole people than King George ever was. Are we willing to make room for those sort of counter narratives? Ultimately that is what’s required to make room for people of difference in our lives.

Note: if you’re interested in learning more about the Revolution of 1688 (if it can even be called a Revolution) check out the Glorious Revolution episode of British History’s Biggest Fibs with Lucy Worsley.