Travel Notes from Pastor Stephen: And the Walls Came Tumbling Down

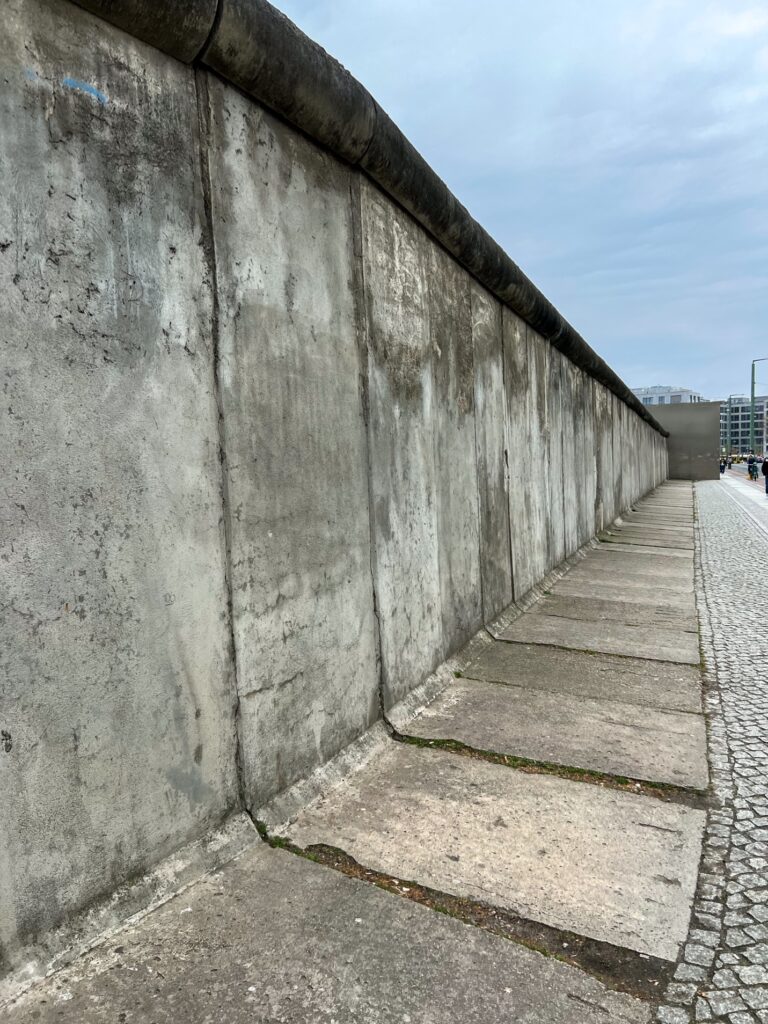

April 20, 2023Courtney and I had the opportunity to visit some of the remnants of the Berlin Wall and the official Berlin Wall memorial over the last couple days. For a long time, the wall was the city’s premier tourist destination and perhaps Berlin’s most famous structure. While the wall is gone, its ghost remains in the form of rubble, souvenir pieces that are scattered throughout the world, and a few places where the remnants remain to remind Berlin and the world of what Germany was, is, and still can be.

An agreement made by the victorious Allied forces of WWII at the Potsdam Conference of 1945 carved Berlin into sectors controlled by each nation. Part of the agreement was that military forces could move freely between the sectors.

In subsequent years, Berlin became a strategically important Cold War bargaining chip – the European ground zero of the conflict between East and West.

The western sectors became the “shop front window of the western world.” Residents were paid extra for living in the shadow of the Soviet Union and were exempt from required military service.

In the Eastern sector of the city, the East German government brought law and order — and fear — to the population. The Soviet Union sought to establish a Soviet satellite representing the aims and interests of Moscow. The Stasi, or secret police, was one of the largest spy networks in the world. There was one Stasi agent for every 68 residents in East Berlin. But East Germany also wanted to show the world the benefits of the Communist State, so they embarked on some ambitious building projects like the TV Tower in Alexanderplatz.

You can see the remnants of the wall everywhere in Berlin. Even where the wall is gone, there are special bricks along roads and sidewalks that mark where it once stood. It still carves up the city: the different districts still each have a unique character.

Wim Wenders, in 1987 wrote, “For me visits to [Berlin] over the past 20 years have been the only genuine experiences of Germany. History is still physically and emotionally present here… Berlin is divided just like our world, our time, and each of our experiences.”

Our world, our nation, our communities and even churches are divided. Our lives are divided between obligations, desires, jobs, and families. What gives me hope is that the wall came down, not through military might, or governmental pressure, but through the persistent will of the people. We can overcome.

We learned stories of people building tunnels under the wall to help friends and family escape East Germany. We saw pictures of people who jumped out of buildings when the wall first went up and an East German police officer, Conrad Schumann, who jumped the barbed wire. Often those stories didn’t have happy endings, and the family they left behind were punished by the East German authorities or they themselves were psychologically tortured even while in West Germany by having to live with constant fear and intimidation from the Stasi. For example, they’d send agents to just break into someone’s house and move things around. Conrad Schumann, the man who jumped the wire, died by suicide shortly after the wall came down.

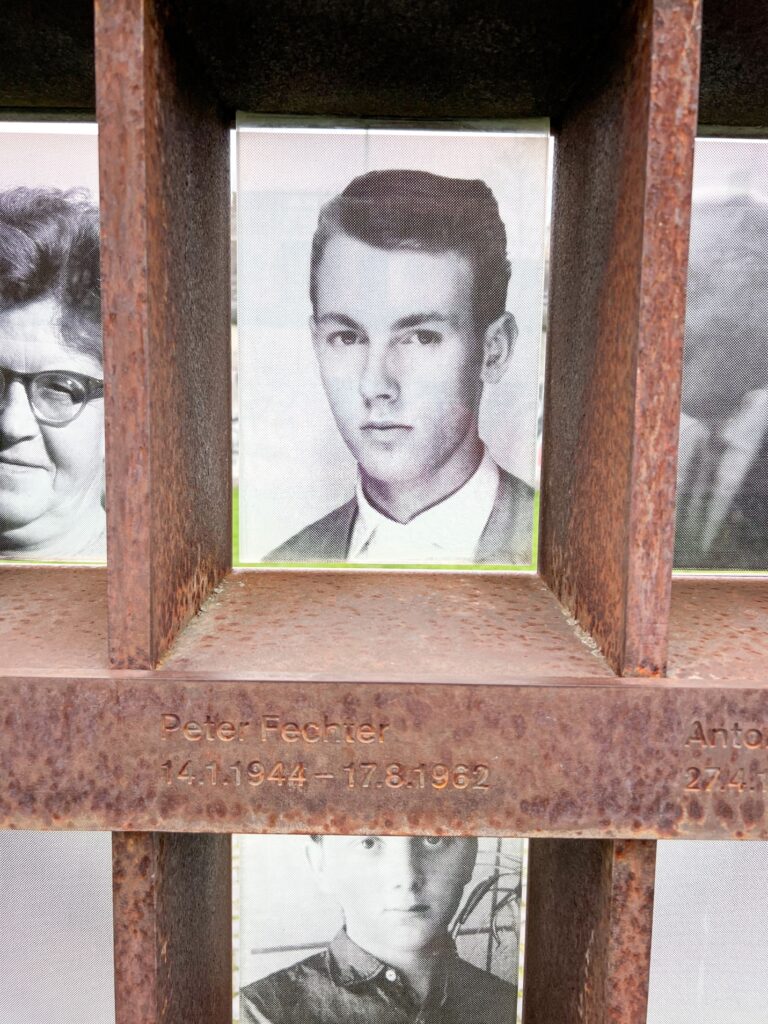

We visited the one place where the full wall remains, which includes a watchtower and two walls with the death strip in between. There were even places where a third wall stood. As Courtney said, “It’s more the Berlin Walls than the Berlin Wall.” East Germany made it really hard to escape. At least 140 people died trying to cross the wall, but that doesn’t count those killed before they made it to the wall, or those who died after crossing. We saw a memorial to all 140 with their names and pictures. Courtney remembers her dad sharing the story of Peter Fechter, an 18-year-old boy, who was killed trying to cross the wall in 1962. He remembered seeing it on the news when he was a young boy. Perhaps you remember seeing the video footage, too.

The wall was a defining thing for Berlin and for Germany. I still remember learning in school about both East and West Germany. I also remember when the wall came down.

I shared the story of Lutheran pastor Christian Führer last fall in a sermon. He believed that the wall that divided East from West was evil and that human freedom was not just a political issue but also a theological issue. So, he began hosting weekly prayer services for peace.

The gatherings at the church were small at first, but once word spread, the crowds grew to the tens of thousands. And then, in October 1989, the Monday-night prayer service culminated in a standoff between this peaceful resistance and the powerful Communist Party. The pastor admonished the demonstrators to be nonviolent. “Put down your rocks,” he preached. So the demonstrators carried candles instead.

And when the Communist Ministry for State Security arranged to occupy more than 500 seats in the church during the Monday prayer service, more than 70,000 peaceful citizens gathered in the streets. Meanwhile, heavily armed security officials waited for instructions from Moscow and Berlin on when they could subdue the demonstrators. They were ready to exercise their power and control. But the order never came, and the police gave up.

The security chief who desperately wanted to subdue the rebellion by force was later shown on film as he stared out at the crowd in front of his headquarters—the crowd whose freedom march had begun in the church, the crowd who had heard the prophetic witness of a pastor emerging from decades of oppression saying, “Let’s move forward in peace,” the crowd so enormous that it stirred fear in the incredibly powerful chief of security, with his tanks and tear gas and firearms. And yet, in that potentially explosive moment, the security chief ready to unleash his armed guards was found saying, “We planned for everything. . . . We were prepared for everything, everything—except candles and prayer.”

The Berlin Wall came down less than a month later. There are other stories like these that speak to the persistence of hope and peace in the human spirit. Stories of people who were able to cross the wall and those who continued to protest and push for its removal. It’s easy to let the human capacity for evil dominate our thinking, but we would do well to remember that the wall came tumbling down.

I learned the story of Harald Jaeger who, for many Germans, is the man who opened the wall because he defied his superiors’ orders and let thousands of East Berliners pour across his checkpoint into the West. He said he didn’t really open the wall, it was the people who stood there who did it. The will of the people was so great, he had no alternative.

It remains me of a quote by Carrie Chapman Catt who was a suffragette: “When a just cause reaches its flood-tide… whatever stands in the way must fall before its overwhelming power.”

Those people had come to his crossing at Bornholmer Street after hearing Politburo member Guenther Schabowski mistakenly say at an evening news conference that East Germans would be allowed to cross into West Germany. For East Berliners longing to go to a part of their city that had been off-limits for 28 years, this was welcome news. Schabowski was a member of the ruling party, so it was assumed that what he said was law.

But Jaeger had always been told that the Berlin wall was a “rampart against fascism.” He cheered when it went up. As a communist who served in the army, he was doing his duty and was fighting the good fight against the bad guys. How often do we think we’re doing the right thing because of what we’ve been taught and how we’ve been raised, only to find out it was never so clear cut? Do soldiers ever think they are “the baddies”?

At first, between 10 and 20 people showed up at Jaeger’s crossing right after Schabowski’s news conference. They were waiting for some indication from Jaeger and the guards that it was okay to cross, but none was given. It wasn’t long before crowd grew to 10,000 shouting: “Open the gate!”

Jeager’s orders were to send the people away, but he knew that was unlikely. He had only ever had to fire one warning shot in the 25 years he worked at the wall, but he worried the crowd could grow unruly and people would get hurt, even if it wasn’t from guns.

To ease the tension, he was ordered to let some of the rowdier people through, but to stamp their passports in a way that rendered them invalid if they tried to return home.

But this only fired up the crowd more. They could see freedom and a better day: it was so close. Despite orders from his higher ups, Jaeger eventually ordered his guards to allow all East Berliners to travel through.

He estimates that more than 20,000 East Berliners on foot and by car crossed into the West at Bornholmer Street. Some curious West Berliners even entered the east.

People crossing hugged and kissed the border guards and handed them bottles of sparkling wine, Jaeger recalls. Several wedding parties from East Berlin moved their celebrations across the border, and a couple of brides even handed the guards their wedding bouquets. I imagine it looked a bit like the scene forever immortalized in the picture from Times Square on VJ Day in 1945. There is such ecstatic spontaneous and generous joy when peace breaks out.

What I’ve found about stories of peace throughout the world is that it’s often the everyday people who play critical roles, and the masses. Peace doesn’t happen because of a few political leaders, though they certainly have a role to play. Peace and reconciliation happen when the people not only desire it: they demand it and work for it with humility and grace.

The wall is gone. Only a few remnants remain to remind the world of Berlin’s past hardship and triumphal reunification. I’m glad there are places like the Berlin Wall Memorial to visit because they aren’t just reminders of a divisive and scary Cold War. These places remind us there is hope. We can reunite after divisions: physical, ideological, theological and legal. Peace can break out at any moment. We can find one another again.