Travel Notes from Pastor Stephen: Out of the Ashes

April 21, 2023Today we visited the city of Potsdam, the capital of the state of Brandenburg. On the way we visited the Platform 17 Memorial at Grunewald Station, where thousands of Jewish men, women, and children were deported from Berlin to various ghettos and camps across Germany and Poland.

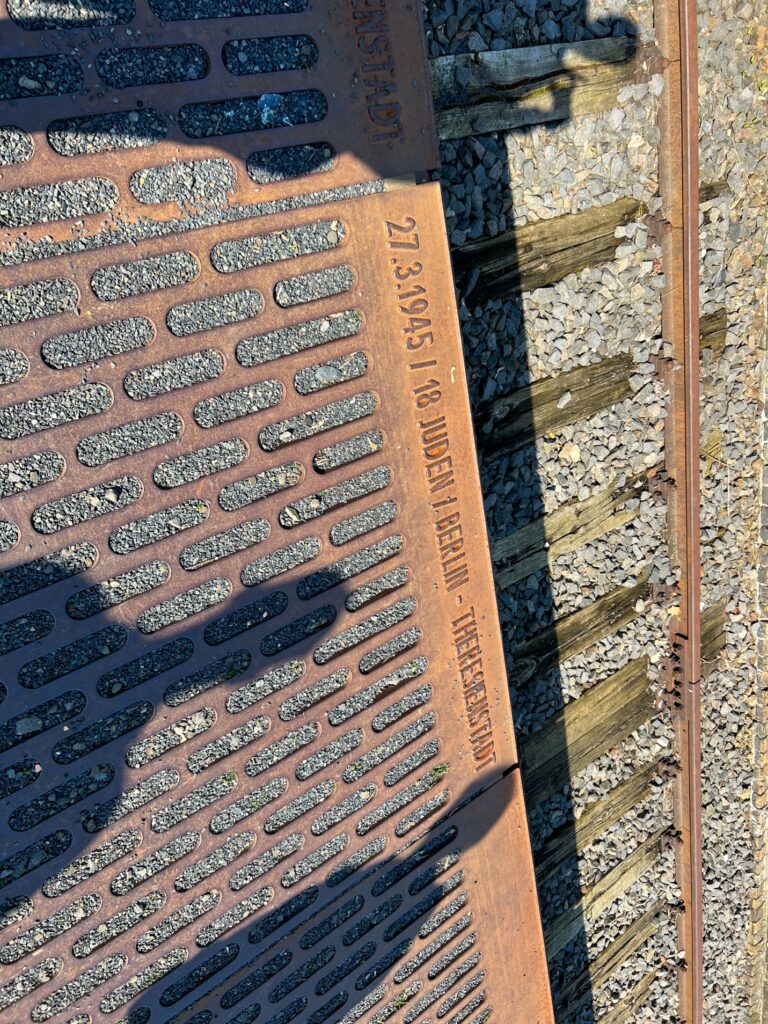

The station, in the sparsely populated outskirts of the city, was chosen so the deportations would not be so visible and there was a less likely chance of public protest and outcry. The first deportation train departed from Platform 17 on October 18, 1941 with 1251 Jews sent to Lodz (a Polish Ghetto) and the last train was sent on March 27, 1945 with 18 Jews sent to Theresienstadt (a ghetto in what is now the Czech Republic). By the end of World War II, more than 50,000 members of the German Jewish population from the Berlin area were deported from this track.

The platform and tracks were abandoned after the war, but in the mid 1990s the Deutsche Bahn AG (German Railroad) were going to convert the old track to a train cleaning station. There was however outcry from the German public about this which forced the Deutsche Bahn AG to confront its own hard history and came to the following realization, which can be found on their website:

Research literature on the role of Deutsche Reichsbahn during the National Socialist regime comes to a unanimous conclusion: without the railway, and in particular without Deutsche Reichsbahn, the deportation of the European Jews to the extermination camps would not have been possible. For many years, both the Bundesbahn in West Germany and the Reichsbahn in East Germany were unwilling to take a critical look at the role played by Deutsche Reichsbahn in the Nazi crimes against humanity. In 1985, the year that celebrated that 150th anniversary of the railway in Germany, the management boards of the railways in both West and East Germany still found it difficult to even mention this chapter of railway history. Neither of the two German states had a central memorial to the victims of the deportations by the Reichsbahn.

This became painfully clear when the reunified railways were merged to form Deutsche Bahn AG. No business company can whitewash its history or choose which events in its past it wishes to remember. To keep the memory of the victims of National Socialism alive, the management board decided to erect one central memorial at Grunewald station on behalf of Deutsche Bahn AG, commemorating the deportation transports handled by Deutsche Reichsbahn during the years of the Nazi regime.

Would the railroad company have come to the conclusion without significant pushback from the public? Probably not. That’s often the case in corporate America, too, but the public can make a difference and force companies and other organizations to take an honest and critical audit of their own histories and determine if reparations, repair, apologies, etc need to be made.

Recently, Princeton Seminary did this after pressure from students and alumni. The Seminary published the results of its historical audit and its role in slavery. If you’re interested to read what they concluded and the actions they decided to take in response, you can read about it here.

Our voices do make a difference. Sometimes the squeaky wheel gets the grease and the persistent voice effects change. Jesus even tells a parable with this lesson (Luke 18:1-8).

The memorial on the platform contains 186 steel plates, each contains the date of transport, point of departure, destination, and the number of deportees. There is a concrete monument by Polish sculptor Karol Broniatowski that displays silhouettes of the victims being marched to the track that was unveiled in 1991.

But the most interesting and hopeful piece of the memorial for me is the one most often overlooked. We wouldn’t have even known about it without our guide. He pointed out a small grove of birch trees in front of the station. In November 2011, the Polish artist Lukasz Surowiec brought 320 birches from the area around the former concentration camp Auschwitz-Birkenau to Berlin, to ‘work against forgetting’. The trees are spread over the whole city, including this small stand outside Grunewald station. What grew out of the very ash of thousands of Jews was finally brought back, replanted, in Berlin. Out of the ash came life and return. The trees and the memories live on. The story lives on, and stories can be one of our most important legacies.

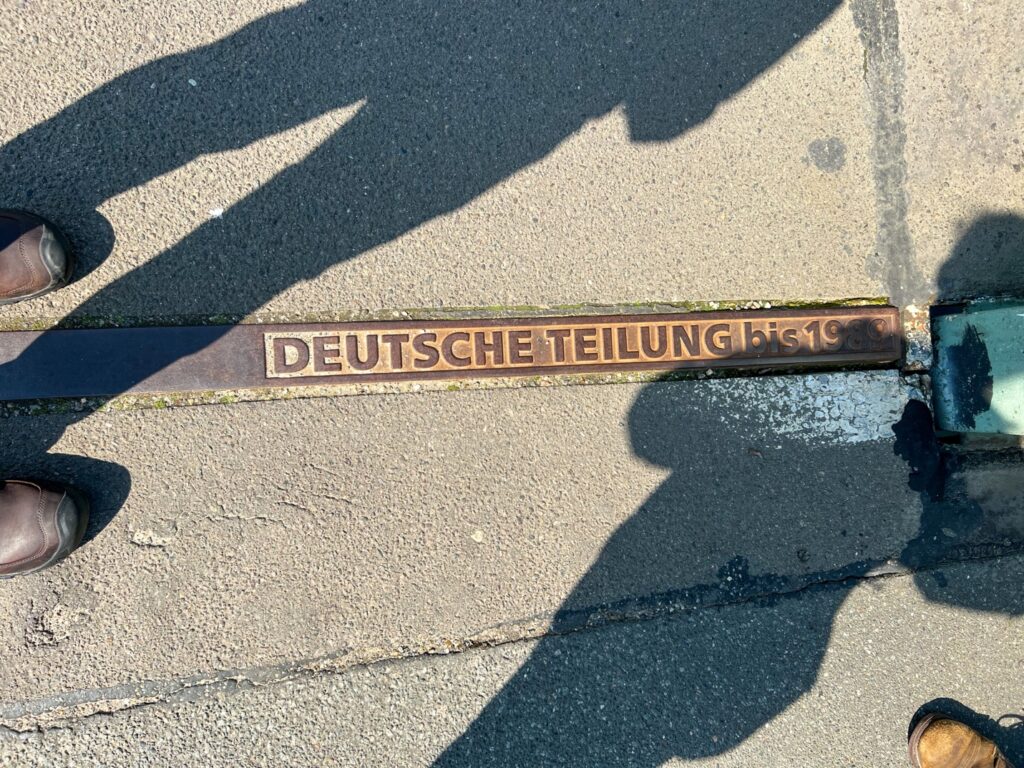

Out of the ashes was a bit of a theme today since we visited Potsdam. We crossed into Potsdam over the Glienicke Bridge, often referred to as the “Bridge of Spies.” The bridge straddled the border between East and West Berlin and, right in the middle of the bridge, a white border line was drawn. Due to its isolated location, the bridge was used to exchange high-ranking spies. The first exchange took place on 10 February 1962. The Soviet spy, Colonel Rudolf Abel, was exchanged for U.S. spy-plane pilot, Francis Gary Powers, shot down in the USSR in his U2 spy plane in 1960.

In Potsdam, we visited Sansoucci (without worry in French), a palace built by Frederick the Great as his summer residence. Frederick the Great was King of Prussia who grew and effectively used the large and advanced Prussian Army to expand Prussian territory and defeat France, Russia, and Austria in the Seven Years war. After the Seven Years War he built the Neues Palace as a giant guest house to show off that he still had money after the war.

Frederick is a rather interesting monarch and person. If you’re interested in history I suggest you read more about him. One of the things I learned was that Frederick is largely responsible for introducing the potato as a staple food in Europe. People pilgrimage to his grave to leave potatoes on it.

Potsdam was in East Germany after the war because of the agreement made between British US, and Russian leaders at the Potsdam Conference (more on that later). Potsdam fell into disrepair because the Soviet Union saw the Prussians as the precursor to what became the National Socialists (or Nazis). Therefore, they didn’t want to take care of the gardens of palaces of the Prussian kings.

In preparation for 1994, the thousand-year anniversary of the town, a lot of money was spent to restore the palaces and gardens of Potsdam. Out of the ashes of the destruction of the war and the ruins of the communist regime, Potsdam has been rebuilt to tell the story of Frederick the Great and others.

We can’t ignore our history. We can’t bury it and pretend it didn’t happen. We can’t ignore the inconvenient and hard parts. It’s all part of our story. We can learn from it and sometimes be thankful for how far we’ve come, how we’ve gotten better, and be thankful for the good that did come from those times. For example, an argument can be made that Fredrick the Great’s Seven Years War paved the way for American Independence because it cost England so much that it didn’t have the time, money, or energy to later invest in a war in America. Also, I like potatoes, so thank you, Frederick. But Frederick was by no means perfect. People suffered because of him and people found success, glory, and better lives because of him.

History is a mixed bag. It’s a teacher if we let it and it’s a part of our story. To truly know ourselves, we must know it.

The last palace we visited in Potsdam was Cecilienhof Palace, built in the Tudor style of an English country house from 1913 to 1917. Kaiser Wilhelm II had the residence built for his eldest son, Crown Prince Wilhelm. Until 1945 it was the residence of the last German crown prince couple Wilhelm and Cecilie of Prussia, but the palace is most famous for the conference held there from July 17 to August 2, 1945, in which the leaders of the US, Soviet Union, and Great Britain met principally to determine the borders of post-war Europe and deal with other outstanding problems.

Despite many disagreements, the three powers found compromises in the wake of war. It was decided that Germany would be occupied by the Americans, British, French and Soviets. It would also be de-militarized and disarmed. The country was to be purged of Nazi leadership and the Nazi racial laws were repealed. Germany was to be run by an Allied Control Commission made up of the four occupying powers.

Stalin was most determined to obtain enormous economic reparations from Germany as compensation for the destruction wrought in the Soviet Union as a result of Hitler’s invasion.

Truman and his Secretary of State James Byrnes insisted that reparations should be exacted by the occupying powers only from their own occupation zone. This was because the Americans wanted to avoid a repetition of what happened after the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Then, it was claimed, the harsh reparations imposed by the Treaty on a vanquished Germany had caused economic crises which in turn had paved the way for the rise of Hitler.

The biggest stumbling blocks at Potsdam were the post-war fate of Poland, the revision of its frontiers and those of Germany, and the expulsion of many millions of ethnic Germans from Eastern Europe. In exchange for its territory lost to the Soviet Union, Poland was to be compensated in the west by large areas of Germany up to the Oder-Neisse Line – the border along the Rivers Oder and Neisse.

Through this process around 20 million people lost their homeland. The Poles, and also the Czechs and Hungarians, had begun to expel their German minorities and both the Americans and British were extremely worried that a mass influx of Germans into their respective zones would de-stabilize them. A request was made to Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary that the expulsions be temporarily suspended and when resumed should be ‘effected in an orderly and humane manner’.

About 14 million Germans lost their homeland. Within a short period of time, they had to be absorbed into the four zones of occupation in Germany. The arrival of forcefully expelled persons created a volatile situation. About one in three Germans lived in emergency shelters for years after the war ended.

The Potsdam Conference fundamentally changed the landscape of Europe. Out of the ashes of war it tried to build something new and stable that would allow for peace. It certainly wasn’t perfect. It’s easy to critique the decisions made, especially with the luxury of hindsight. It paved the way for the Iron Curtain and years of communist oppression for what are now eastern European nations. It dislocated millions and changed borders. There couldn’t have been a perfect answer to all the postwar questions especially with the competing interests of Britain, America, and the Soviet Union.

Sometimes the best we can do is the best we can do. We cannot let the perfect become the enemy of the good. We can learn from mistakes and try to do better, but sometimes all we have are bad and difficult choices and options. We need to be able to offer grace as well as critique to our histories. If ridicule, shame, judgment and guilt is all we walk away with after studying history, then we are studying it wrong. Sadly, that’s how it is often presented. We need to reckon with the wrong, but we need to celebrate the good, too. And we need to recognize that perfect solutions rarely exist.

We also need to remember that rebuilding takes time. Of course, that’s easy to say if we aren’t the ones suffering during that waiting period, but it’s a reality nonetheless. Progress is often in steps. We don’t make one giant leap to the end. We’ve come a long way since WWII. Germany has come a long way, and many of the former communist nations like the Czech Republic (formerly part of Czechoslovakia) have come a long way economically and politically. It’s been a long road, but progress has been made. I think we can celebrate that even if it wasn’t immediate and even if the journey was fraught with pain and suffering. Rebuilding and new life takes time.

This is true of our Christian journey as well. While God’s grace and love is always for us, we don’t immediately turn into the disciples God wants us to be. It’s a life-long journey. We make mistakes and we experience successes. We confess often, we don’t pretend we have no sin. We do not deceive ourselves. But we also should celebrate our growth as children of God. A religion built only on guilt does not lead to life.

My favorite part of today was having dinner with Susan Neiman. It was a riveting conversation that has left me with a lot to think about. She talked about how she’d write her book differently today and new projects she’s thinking about. We talked about how history is taught and how we cannot make guilt the one and only outcome of our reckoning with history. We have to have hope and we have to highlight the heroes, too. I hope I’ll have more time to share some of that conversation with you after I’ve had more time to process it. I am looking forward to reading her newest book soon, and she recommended some interesting looking books as well. It was a valuable conversation that has helped me think more about what is required for peace and reconciliation in our world.